Archive

Shattered Mirror, Stunted Vision and Squandered Opportunities

Two weeks ago, the Public Policy Forum published its report on the state of the news media in Canada: The Shattered Mirror: News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age. It’s an important report, and needs to be taken seriously.

The report’s portrait of the state of journalism in Canada is grim: advertising revenue has plunged in the past decade – due, it claims, to the internet, and to Facebook and Google especially; daily newspapers have been closed, merged or pared back during the same period; many local TV stations face a similar fate; well over 12,000 journalism jobs have vanished; fake news is pouring in to fill the void; and the social ties that bind us together are fraying. All of this adds up not just to a crisis of journalism but a potential catastrophe for democracy writ large, the report intones.

In the report’s view, throughout the 20th Century advertisers, audiences and news organizations shared a mutually beneficial three-way relationship: advertisers got cheap access to large audiences, journalists got paid, and we got our news for next to free because advertisers footed the bill. This literally was the “free press”, and by lucky happenstance, democracy was the better for it.

That’s all coming undone now, though, say the wise counsel of mostly senior journalists and journalism professors huddled around the Public Policy Forum’s new CEO, Edward Greenspon (and former Globe and Mail and Bloomberg News senior editor) who led the development of this report. They conclude with a dozen recommendations designed to turn back the tide. The cornerstones of their policy proposals aim to redirect advertising revenue that is currently flowing into the coffers of Silicon Valley-based internet giants like Google and Facebook back to Canada. Another group of policy recommendations aims to use a proposed new Future of Journalism and Democracy Fund to boost the capacity of professional journalism taking root in emerging digital news ventures and First Nations journalism organizations.

I think that the exercise is potentially useful, and that there’s no need to shy away from the idea that the federal government can adopt supportive policies to bolster journalism and help a democratic culture to thrive. However, this report is badly flawed. All along the way it cherry-picks evidence and gooses the numbers that it does use to make its case. There is also an acute sense of threat inflation that hangs about it. The extent to which Google, Facebook, Silicon Valley and “the Internet” are made the villains of the piece is both symptomatic of how the report tries to harness such threats to preordained policy ends and a framing that undermines the report’s credibility.

The Shattered Mirror also dodges four fundamental issues that hobble both its analysis and policy recommendations:

- Media concentration and the unique structure of the communication and media industries in Canada;

- The impact of the financial crisis of 2008 which, even though its epicentre lay elsewhere, has resulted in a lacklustre Canadian economy ever since. This resulted in a sharp drop in advertising that slammed ad-funded news media and from which they have never recovered, and likely won’t;

- Advertising is no longer the centre of the media economy, and receding ever further from that role by the day, so hinging a policy rescue on recovering so-called lost advertising is out of step with reality and likely to fail;

- The general public has never paid full freight for a general news service and likely never will. Thus, it has always been subsidized, and as the bottom on advertising revenue falls out that source of subsidy will have to be replaced by another if we really are concerned about getting the news we deserve – trying to wrestle money out of Google and Facebook (the report’s central policy proposal) won’t cut it. The proposal to apply the GST/HST to them, with some tweaks, so as to make it apply to all forms of advertising and to earmark these newfound tax revenues to original Canadian content, could help and is, thus, one I support.

Finally, I am skeptical about the “real news versus fake news” frame that girds the report. The language about “vampire economics” is overwrought. Such things give a tinge of moral panic to the report, and taints the analysis and policy proposals. Unless otherwise cited or linked to, the data sets underlying the discussion can be downloaded under Creative Commons principles from the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project’s Media Industries Database. A PDF version of this post is available here.

Chronicling the Crisis: the Public Policy Forum Makes its Case

As the Public Policy Forum documents, advertising revenue has plunged for daily newspapers, and is beginning to fall for television. Addressing “classified advertising” specifically the report states that “three-quarters of a billion dollars a year in reliable revenue vaporized in a decade” (i.e. 2005-2015). Daily newspaper display advertising revenue totaled $1.8 billion in 2006; a decade later it had been cut in half. Altogether, total daily newspaper advertising revenue has plunged by 40% — from $3.3 billion in 2006 to an estimated $2 billion this year. Community newspaper revenue has fallen by $407 million since 2012 (pp. 17-19). Will the last journalist please turn out the lights?

According to The Shattered Mirror, a similar fate is beginning to beset TV. Profits have plunged from 11% for “private stations” in 2011 to -8% last year, for instance (p. 24). Another study by Peter Miller and the Friends of Canadian Broadcasting that hangs about The Shattered Mirror report but which is not cited, worries that, economic trends, and what it sees as a series of wrong-headed decisions by the CRTC, could lead to another 30 local TV stations going dark by 2020.

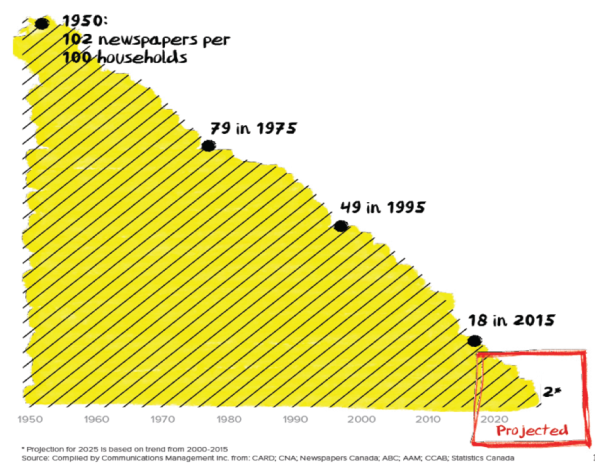

Newspaper circulation has also been cut four-fold from just over 100 newspapers per 100 households to half that amount in the mid-1990s, to just eighteen last year. The paid daily newspaper as we have known it for the past century could be extinct in five years, the Public Policy Forum report warns (p. 15). And as those implications come to pass, fake news is pouring in to fill the void, desiccating the social bonds that tie us together as a nation, as a people, and as a democracy.

Figure 1 below illustrates the point with respect to declining circulation.

Figure 1: The Vanishing Newspaper: Newspapers sold per 100 households in Canada, 1950-2015, projected to 2025

Source: Public Policy Forum (2017), The Shattered Mirror, p. 15.

In addition, twelve thousand journalists and editorial positions have been lost in recent decades, according to figures cited from the Canadian Media Guild. Unifor and the Communications Workers of America also report another 2000 or so positions lost as the massive shift in advertising revenue to the internet guts Canada’s news rooms.

The lost revenue at the root of this carnage, however, the report argues, has not vanished but migrated to the internet. In fact, internet advertising has sky-rocketed from half-a-billion dollars a decade ago to $5.6 billion last year, states the report. This ‘shift’ has benefitted a small number of internet giants based in Silicon Valley, while depriving Canadian news media of the money they need to survive.

The report is emphatic that the free-wheeling early days of the internet have been eclipsed by the rise of a few foreign digital media giants and a process of “vampire economics” whereby those giants, and Facebook and Google in particular, are sucking the lifeblood out of “real news”. As the report states, the internet giants are getting an incredibly “sweet deal”: “leverage the news others finance and grab the advertising that used to finance that news” (p. 31). But as Facebook and Google get rich, journalists, news organizations and, yes, us and democracy are being robbed blind. The report is explicit that only once this lost advertising revenue is brought home, will all be well: the so-called crisis of journalism will be solved and democracy saved.

Some of that money flowing south needs to be clawed back and the two behemoths need to learn to show more respect for the news content that they have used to build their empires, the report stresses. Not only do we need to do this, we can do it if policy-makers gather up the political will needed to change the Income Tax Act to make advertising on Canadian internet news sites tax deductible but not foreign websites (as has been done for newspapers and broadcasting since 1965 and 1971, respectively). GST/HST should also be applied to foreign internet companies that sell advertising and subscriptions in Canada, e.g. Google, Facebook and Netflix. These measures would cost little and raise $300-400 million that could be used to fund public policy initiatives to strengthen professional journalism (p. 84). In addition, Facebook and Google must be made to play an active role in stemming the tide of “fake news” flooding into our country while giving priority to Canadian news sources. In other words, they must be made to act more like responsible publishers (p. 97).

Tunnel Vision, Goosing the Numbers, and “Off Limits”

Advertising-supported journalism is not the ‘natural order of things’.

The case that the authors of The Shattered Mirror make about the severity of the crisis of journalism is impressive at first blush. Ultimately, however, it is neither convincing nor credible.

Its fixation on advertising revenue, for instance, assumes that it has always been an integral part of the natural journalistic order of things. It has not. Advertising revenue soared from being less than half of all revenue to account for between two-thirds and 90% of revenue at big city newspapers in the US and parts of Europe between 1880 and 1910, and in Canada two decades after that (Sotiron, 1997, pp. 4-7). While the advertising-supported model of journalism carried the day during the ‘industrial media age’ for much of the 20th Century thereafter, there is little reason to believe that it will or even should have an eternal lock on being the economic base of the media forever into the future – the Public Policy Forum report’s wishful thinking notwithstanding.

Moreover, while advertisers tied their fortunes to the commercial media model for close to a century, they had no special love for the media or the journalistic functions they perform, per se. Instead, they did so because it was the most cost-effective way to meet their needs. New and better means to deliver up audiences to advertisers at a much lower price have been developed since and, unsurprisingly, businesses have reached for the newest tool in their toolbox: the internet. This is an uncomfortable truth that the report refuses to acknowledge, and thus to engage with. Not even King Canute could turn back that tide, and nor should we want him to even if it was possible. We have to find a better way to pay for the news for just this reason and also because, for the most part, Nasreen Q Public never has been willing to pay for a general news service.

Advertising is being eclipsed by “Pay-per” media.

Advertising is also becoming a smaller and smaller part of a bigger and bigger media economy. It has long been eclipsed by the “pay-per model”, or subscriber fees, where people pay directly for the communications and media they use. Subscriber revenue outstripped advertising by a 5:1 margin for the ‘network media economy’ in 2015 (see here for a definition of the ‘network media economy”, p. 1). “Pay-per media” are now the economic engine of the media economy. The Shattered Mirror, however, does not seem to recognize this and thus examines the problems facing journalism through the wrong end of the telescope, e.g. advertising.

Take TV specifically. The report states that “TV revenue is start[ing] to drop”. The statement is true for advertising-supported broadcast TV, but not for TV as a whole. Subscription revenue for specialty and pay channels, OTT services like Crave TV and Netflix as well as and cable TV now account for three-quarters of all revenue, and for the most part continue to grow. Annual funding for the CBC makes up the rest, i.e. just over 5%. The Shattered Mirror draws general conclusions about the supposedly sorry state-of-affairs for TV writ large based on a small as well as diminishing part of a larger vista. The advertising-supported part of TV accounted for less than half of all revenue in 2015 (e.g. 42.6%). It is in trouble, but again this is a fraction of the whole picture.

In addition, blaming “the internet” ignores other potential explanations for the problems that do exist. Why, for example, is broadcast TV not in dire straits, and in some cases making a bit of a comeback in the US and some other countries (see FCC and Ofcom, for example)? The report does not bother to ask, let alone explore such realities, for reasons that will become clear in a moment (hint, it has to do with media concentration and the unique structure of the media and communication industries in Canada, issues that the report explicitly eschews).

Having left out the fastest growing and biggest segments of the media economy – the ‘pay-per’ segments – and painted a picture of rapacious foreign internet giants stealing away advertising revenue from Canadian news media organizations, the report ignores another fundamental fact that does not fit the story it wants to tell: advertising revenue across the entire economy has stagnated for close to a decade. Moreover, per capita advertising spending dropped from $371 per person in 2008 to $354 in 2015 – the last year for which a complete set of data is available. TV advertising specifically has stayed flat in absolute terms while falling from $102 per person in 2008 to $94 last year (see here). That said, however, and unlike the report’s claim to the contrary, total TV revenue continues to grow, and indeed revenues for specialty and pay TV as well as OTT services have soared over the years based on subscriber revenues, albeit with slow growth in some aspects of some of these services in the last year or two.

In addition, the report’s claims regarding the steep decline in “private station” profits from 7.3% to -8% between 2011 and 2015 is misleading (p. 16). The statement implies that it applies to TV in general but in fact refers only to the smallest and shrinking part of the TV landscape: commercial broadcast TV. Operating profits for pay and specialty TV — the biggest and still growing segment of the TV landscape — were 20.8% in 2015, however. For cable TV and radio, they were 19% (see CRTC here, here and here). Meanwhile, operating profits at Bell Canada Enterprises’ media arm were 25% in 2015 and an eye-popping 40% for the company as a whole – four times the average for Canadian industry (Statistics Canada). Figure 2 below illustrates the point.

Figure 2: Bell Media Operating Profits, 2015

Source: BCE, 2015 Annual Report, p. 130.

Source: BCE, 2015 Annual Report, p. 130.

Parenthetically, it is also important to note that Bell is the biggest, vertically-integrated TV operator in Canada by far, accounting for roughly 30% of all TV revenues and 28% of total revenue across the network media economy. Ignoring conditions at a company with this clout across the media economy is negligent, but also part of a tendency in this report to selectively invoke a small part of the picture to fill in a portrait of catastrophe of a larger kind. In terms of the rules of rational argument, this pattern is a type of spurious reasoning called an “indexical error”. The report is chock-a-block full of such examples, which lends to the impression that the report’s authors are goosing the numbers.

Let’s consider a few other claims made about collapsing circulation and the “vanishing newspaper” and the scale of journalistic job losses, before turning to its willful refusal to deal with fundamental considerations about how the unique structure of communication and media industries in Canada directly bear on its topic but which are wholly ignored.

The Vanishing Newspaper?

These examples are not innocent. They are part of a process of “threat inflation” with the aim of buttressing the case for the policy recommendations on offer. Much the same pattern can be seen in the report’s depiction of circulation trends for daily newspapers. Now, make no mistake about it, the picture cannot be spun as a good news story. That is not my point. Looking at the issues from different angles and a more measured and nuanced view reveals that that things are far from rosy, but they are not the catastrophe that The Shattered Mirror makes them out to be. The reasons why things are as bad as they are also demands a richer and more multidimensional explanation than the ‘single-bullet’ explanation the report offers: blame the internet (and Facebook and Google). To illustrate the point, let’s return to Figure 1 above, which is repeated below to make the job easier.

Figure 3: The Vanishing Newspaper: Newspapers sold per 100 households in Canada, 1950-2015, projected to 2025

The message of the Figure 3 is clear: newspapers have undergone a precipitous decline, and could vanish altogether soon. Indeed, already by 2015, the number of newspapers sold per 100 households was one-quarter of what it was in 1975. By this measure, the relentless decline and seemingly inevitable outcome look really, really bad – catastrophic even.

Now, let’s expand our measures to look at things from four additional angles: (1) total number of newspapers sold per week per person; (2) total number of newspapers sold per week per household; (3) total circulation; and (4) by revenue – shown for both total revenue and just advertising revenue. My numbers start in 1971 because that is the earliest date for which I could gather data fit for the task, but as far as I can tell that has no impact on the main point. And just to make my main point clear, it is that the Public Policy Forum’s Shattered Mirror report has selectively chosen a measure that paints the worst-case scenario rather than a nuanced, multidimensional picture of a situation that is bad enough that it doesn’t need to be exaggerated. In other words, I am depicting a strategy of policy argumentation that I call “threat inflation”.

Figure 4, presents two sets of data, one for the number of newspapers sold per week per person and another for the number of newspapers sold per week per household – both for the period from 1971 to 2015 (the latest year for which figures are available).

Figure 4: Per Household and Per Capita Decline of Daily Newspapers Circulation in Canada, 1971-2015

Sources: Newspaper Canada; Statistics Canada.

Figure 4 confirms that newspaper circulation has been in long-term decline and there appears to be nothing on the horizon to turn that around. If we care about newspapers because they are one of the main sources of original journalism – as I emphatically do – this is a ‘bad news’ story. Yet, while the decline shown in Figure 4 is obvious – indeed, circulation was cut in half over the period covered on the basis of total copies per week per household – that is half the rate depicted by The Shattered Mirror. The difference is likely due to the fact that the number of people per household has declined over time, so fewer people per household means fewer newspapers in each house even before we take declining circulation into account — versus the “vanishing newspaper” scenario.

Now, let’s look again from the vantage point of circulation per capita shown in Figure 4 above. It also shows that circulation levels have declined steadily since 1971, but by only about 35% versus the four-fold collapse The Shattered Mirror depicts. This is what I mean by threat inflation: choosing methods and numbers that inexorably lead to the worst-case conclusion.

Now let’s look at things from the vantage point of total newspaper circulation because if you’re in the journalism business, a key consideration has got to be not how many daily newspapers you can sell per person or per household but in total. Figure 5 depicts the trend over time.

Figure 5: The Rise and Fall of Newspapers Circulation in Canada, 1971-2015

Sources: Newspaper Canada; Statistics Canada.

Figure 5 shows that, in terms of sheer volume, newspaper circulation continued to rise until 1990 (versus falling steadily from 1950). It has fallen since, albeit in fits and starts. And obviously, against a population that has swelled from 22 million to nearly 36 million over the timeframe covered, circulation is shrinking in relative terms, which is the point of the earlier figures. Yet, the point is once again that this is a ‘bad news’ story but not a catastrophic one, and the fact that circulation peaks in 1990 and then goes down in fits and starts thereafter also raises interesting questions about timing that are ignored by the Public Policy Forum report, again likely because they don’t fit the tale of doom and gloom that it is mobilizing, but which I will return to below.

Now let’s turn from circulation to revenue data to see what things look like from this vantage point. Figure 6 does that based on stand-alone advertising revenue and all sources of revenue (advertising, subscription and other, including digital/internet).

Figure 6: The Rise and Fall of Newspapers Revenue in Canada, 2000-2015

Sources: Newspaper Canada; Statistics Canada.

As Figure 6 shows, advertising as well as subscription and other sources of revenue continued to rise for newspapers into the 21st Century. Indeed, while circulation was in decline regardless of the measure used, revenue continued to climb. Revenue peaked in 2008 at $3.9 billion and $4.7 billion, respectively, for advertising and ‘total’ revenue measures — a crucial point in time for reasons that will emerge in a moment. Revenue has plunged since, with newspaper advertising revenue falling to $2.3 billion (a drop of 40%) and total revenue to $3.2 billion (a drop of 32%) in 2015. This is bad.

Thus far, none of the measures reviewed leads to a ‘good news story’, but each of them in their own way change the magnitude, timing and potential causes of the problem. Of utmost importance is that there is no downward spike in the fortunes of the press on any of these measures that coincides with when the internet takes off, either in its dial-up phase in the mid- to late-1990s or when broadband internet took centre stage in the early-2000s. Given this, the internet – and Facebook and Google – cannot be the villain of the piece that The Shattered Mirror (and so many lobbying the government from the “creator” and “cultural policy” groups) makes it out to be.

In fact, this is not news. While such claims are common, that they are wide of the mark is well known. One of the world’s top media economists, Robert Picard of the Reuters Institute of Journalism at Oxford University, for instance, has made this point for much of the last decade. I have too with respect to Canada and across the world. That neither circulation nor revenue dives downward with the arrival of the internet cuts to the heart of the central claim in The Shattered Mirror. Yet, like so much of the evidence that does not fit its “sky-is-falling-because-foreign-internet-giants-ate-Canadian-news-media’s-lunch” rhetoric, this evidence doesn’t make the cut. If all of this is correct, we must also change our diagnosis and policy proposals accordingly.

Alternative Explanations: Stagnating Advertising Revenue and Vanishing Jobs

Not only does newspaper revenue not spike downwards with the advent of the internet, the onset of economic woes for advertising supported media do not coincide with the time frames that the Public Policy Forum report identifies, typically 2005 or 2006 for newspapers and ‘recently’ for TV. The upshot of its misdiagnosis is to effectively carry on with the ill-fated case its authors want to make while avoiding another possible – and I believe far better — explanation for the woes they describe: the impact of the financial crisis in 2008 and economic instability that has followed ever since.

Figure 7 below illustrates the point by showing a sharp downward kink in revenue for nearly all the media sectors it covers since 2008. This reflects the impact of the global financial crisis on the media economy. At this point in time, advertising revenue falls for total TV advertising revenue, broadcast TV, newspapers, radio, out-of-home advertising and magazines. The impact even hits internet advertising and pay TV services, as their revenue growth flattens temporarily before rising again a year or two later.

Figure 7: The Impact of the Financial Crisis and Economic Stability on Media Revenue (millions$), 2004-2015

Sources: IAB.canada 2015 Actual + 2016 Estimated Internet Ad Revenue; TVB (2016). Net Advertising Volume, CRTC Communications Monitoring Report.

Total advertising revenue fell by 7% from $11.6 billion to $10.8 billion. It rose again the next year to recover the lost ground but unevenly. Tellingly, however, advertising revenue has fallen from $371 per person in 2008 to $354 on a per capita basis in 2015, and from $102 per Canadian to around $94 for TV– as indicated earlier.

The recovery that has occurred has taken place in fits and starts and has been very uneven across different media sectors. The long-term effects of that appear to be three-fold. First, it has gutted newspaper advertising revenue. Second, it has propelled the shift of the economic base of TV from advertising to subscriber fees. Third, amidst the upheaval, the internet has consolidated its place at the centre of advertising revenue. It now accounts for more than a third of all advertising revenue (36.2%) in a stagnating pool of advertising money.

Again, none of this is a mystery, except to those who work the policy apparatus here in Canada, and there is no mention of it in The Shattered Mirror or indeed in any of the policy reports being wheeled into action by the myriad of groups vying to shape the outcomes of Heritage Minister Melanie Joly’s Canadian Content in a Digital Age review. Beyond this cloistered community, however, the fact that the fate of advertising-based media turns tightly on the state of the economy – and indeed, is something of a canary in the coal shaft for it – is reasonably well known and discussed by media economists from across the political spectrum. This has been the case for many, many years (see, for example Picard, Garnham, Miege, Vogel but also any media economics text). That the subject is not even broached by the Public Policy Forum’s report is a measure of the extent to which it ignores evidence and ideas that don’t fit the story it wants to tell, and of a piece with its methodological tactics throughout the report.

In sum, it is a mistake to focus on a ‘silver bullet’ explanation of complex issues like the one before us. The fixation on the negative impact of the internet and the two villains of the piece, i.e. Google and Facebook, is misplaced. In short, advertising revenue has taken a nose dive because the economy has been shattered not because Tyrannosaurus Digital Media Rex Google and Facebook ate the news media’s lunch.

A Catastrophic Loss of Journalists?

Just as the data with respect to declining circulation and lost revenues in The Shattered Report is circumspect, so too are the figures that it cites for the number of journalist and editorial positions lost over the years partial and incomplete. The report says that between 12,000 and 14,000 such positions have been lost over an indefinite period that sometimes stretches back to the 1990s but with a stress on recent events. The figures cited are based on a tally of headlines announcing such cuts and more systematic record-keeping by the Canadian Media Guild, Unifor and the Communications Workers of America. I have no doubt that the human impact of the losses they document are real and severe.

However, there are two short-comings of the data presented. For one, it is based on headlines and record keeping that do a great job chronicling jobs lost but a poor one at keeping track of those gained. Second, Statistics Canada data depicts a wholly different picture. The report needs to at least explain why the Statistics Canada data offers a less satisfying account of the conditions than the sources it relies on. It does no such thing. In fact, and once again consistent with a pattern, the authors ignore this data completely.

According to Statistics Canada data the number of full-time journalists in Canada has not plummeted. In fact, it has crawled (stumbled?) upwards from 10,000 in 1987 to 11,631 in 2015. Figure 8 below illustrates the point.

Figure 8: Journalists vs the PR, Advertising and Marketing Professions,

1987-2015

Sources: Statistics Canada (2016) Employment by occupation: 1123 Professional occupations in advertising, marketing and public relations and Statistics Canada (2016). Employment in Journalism occupation, by province. Custom LFS tabulation. File on record with author.

While this is a small increase, it is an increase all the same, and counter-intuitive as well. Things that are counterintuitive beg you to explore why they are so. Also consider that after years of a sluggish economy in the early-1990s, and extensive consolidation and cut backs in the latter part of the decade, the number of working journalists fell to a little over 6,000 (1998). If we take that as our base, the number of working journalists has nearly doubled since and, consequently, the period looks more like one of modest growth rather than a catastrophe.

Of course, this small increase should not be over-played. It has occurred against the backdrop of a media economy that has quadrupled in size. Even if the number of journalists has stayed relatively steady rather than collapsed, this still means that their numbers have shrunk relative to the size of the media economy. In other words, similar amounts of journalistic resources in a much bigger media pie constitutes a relative decline. This is cause enough for concern without the hyperbolic rhetoric that The Shattered Mirror leans on.

In addition, whatever modest growth has taken place has been vastly out-paced by the number of people working in the PR, advertising and marketing professions. Whereas there were four people of the latter type for every journalist in 1987, by last year, the imbalance had swelled to 10:1 — a triumph of the persuasion professions over journalism, which again is cause enough for commentary and concern. Yet again, the Public Policy Forum’s report is silent on the point.

My point, once again, is not to assert that the Statistics Canada data is definitive on the matter of journalistic and editorial job losses. Instead, it is to highlight how selective The Shattered Mirror report is. The pattern is one where evidence that fits its grim vision of the current state of journalism in Canada is highlighted while that which cuts across the grain is either downplayed or ignored completely.

Blindspot: the Media Concentration Problem

The Shattered Mirror also gives short shrift to the idea that media concentration and the structure of the communication and media industries might be a significant factor giving rise to the woes besetting the news media, except for the highly concentrated nature of internet advertising. As Greenspon told J-Source, media concentration is just not “the existential risk to media that it was for a number of years”. However, the report is more than willing to turn the screws on Facebook and Google’s dominance in the one market — online advertising – where they undoubtedly and overwhelmingly do dominate, while simultaneously turning a blind eye to high levels of concentration in several media markets and in terms of vertical- and diagonal-integration across the telecoms-internet and media landscape in Canada.

By The Shattered Mirror estimation Facebook and Google account for two-thirds of all internet advertising spending in Canada. It also shows that internet advertising has become more concentrated over time, not less: the top ten companies took 77% of all internet and mobile advertising revenue in 2009, but by 2015 that number was 86%. The top twenty companies accounted for 90% (pp. 31-32). There is evidence that these levels are growing. I agree with this part of the report’s analysis, not surprisingly since it draws heavily on data and estimates from the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project that I direct.

The same claims have been circulated by those who have advised or influenced the direction of The Shattered Mirror. Ian Morrison, the head of the Friends of Canadian Broadcasting, summarized the key claims being made as follows, for example:

Based on data from the Canadian Media Concentration Project [sic] at Carleton University we estimate $5 billion of Canadian advertising goes to foreign-owned internet companies such as Google and Facebook . . . . With the Interactive advertising Bureau projecting $5.55 billion in overall internet advertising revenue . . . for 2016, we estimate that almost 90 percent of what Canadian advertisers spend on digital ads will leave the country.

In an interview with the Globe and Mail’s Simon Houpt, Greenspon asserted that Google and Facebook alone “take in about 85% of digital ad dollars” – although that number conflicts with others elsewhere in the report. However, the numbers do seem to regularly get mixed up, so that it is not quite clear if we are talking about just Facebook and Google or some ‘other’ foreign internet giants as well.

My main concern is that claims that foreign-owned internet companies will take $5 billion in projected internet advertising revenue for 2016 – or 90%, and that Google and Facebook alone account for up to 85% of the total — out of Canada are stretching the available data beyond what can be reasonably supported. They build estimate upon estimate, jump through hoops, and draw questionable inferences to come up with these figures (see pp. 30-31).

The CMCR Project data estimates with reasonable confidence that, combined, Google and Facebook accounted for about $3.1 billion, or two-thirds, of a total of $4.6 billion in internet advertising revenue in 2015 – the last year for which final figures are available. There’s some room for adjustment either way. Based on what we do know the figures touted in The Shattered Report and elsewhere do not seem credible, even if repeating them in one venue after another seems to have given them an aura of holy writ.

This is especially troubling because the estimates offered not only extrapolate from the limited base of what we do know but serve as a springboard to The Shattered Mirror’s #1 Policy Recommendation:

Policy Recommendation 1: Change the Income Tax Act to make advertising on Canadian internet news sites tax deductible (as has been the case for newspapers and broadcasting since 1965 and 1971, respectively) while applying a ten percent withholding tax for advertising on foreign websites. The key aim is to open a new “revenue stream of $300 to $400 million that would be used to finance a special fund” much along the same lines as the existing levy on cable TV companies is used to fund Canadian content (pp. 83-84).

At a bare minimum, if their numbers are off, so too are these estimates.

Overall, the path to this policy recommendation and the proposal itself is flawed for a handful of reasons. For one, as just indicated, the available evidence is insufficient to support the report’s #1 policy proposal. Second, even if the numbers were right (or close), both the analysis and the policy proposal ignore the structural shift in the economic base of the media from advertising to the pay-per model described earlier, while assuming advertising has and should forever form an integral part of the natural order of the news media. Third, it appears to swap the bad idea of an ISP tax levied against wireline- and mobile wireless internet access providers (which, not coincidentally, are Canadian) for a “platform levy” applied against ‘foreign digital platforms’, e.g. Google and Facebook. If this is correct, the bait and switch on nationalistic grounds is objectionable on its own.

The bigger problem, however, is that the recommendation seeks to take an approach that has been applied to limited (single) purpose broadcasting distribution systems for the past half-century and apply it to general purpose internet platforms that host, store and facilitate a dizzying and ever expanding array of content, applications, services and uses. And it does so in the name of supporting a narrow range of content – “real news”, as the report calls it – that constitutes a tiny sliver of what people use and enjoy these platforms for. Whether applied to ISPs or digital platforms, the idea that the multitude of uses that people make of the internet should be harnessed to promoting journalism (or Canadian content generally) – no matter how important – is objectionable. In terms of a common test applied to free speech cases, while the goal being sought is legitimate, the means being promoted to achieve it is akin to a sledge hammer when what we need is a scalpel.

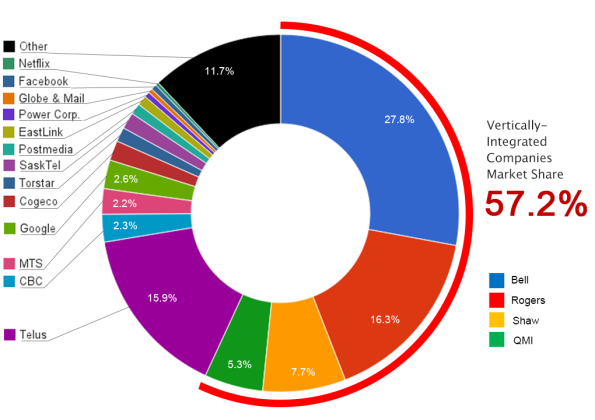

Finally, while the report does a good job of documenting the extent of the internet giants’ dominance of the online advertising market, both the analysis and proposal exaggerate the extent to which Google, Facebook and other ‘foreign internet giants’ influence reaches across the media landscape in Canada. By ignoring the latter, the effect is to minimize the extent to which media concentration and the uniquely high levels of vertical and diagonal integration between telecoms-internet service providers and other key areas of the media, especially television, have given rise to homegrown problems rather than the debilitating “vampire economics” imported from afar (the following paragraphs draws heavily from a series of CMCR Project reports: see here, here and here for more details and elaboration).

How to Look at Media Concentration

Using what I have learned as the “scaffolding method”, it is essential to look at the state of competition and/or concentration in one media sector at a time, group the different sectors together into reasonable clusters such as “content media” (e.g. newspapers, TV, radio, magazines, etc.), “connectivity media” (e.g. internet access, mobile wireless, etc.) and “internet media” (e.g. search, internet advertising, social media, browsers, etc), and then group everything together so as to get a view of the network media economy in its entirety. One must also look at trends over time, and in comparison to other parts of the world.

The Shattered Mirror report does nothing of the sort, and so it paints a picture sloppily with a broad brush, declaring that media concentration is not a problem when it feels fit to do so, but a worrying concern where that suits its purposes, i.e. in the areas that Google and Facebook dominate. Ultimately, there is no overarching sense of how everything fits together, and so the image drawn is arbitrary, and wholly dependent on the whims of the observer.

So, let’s try to get things straight in a minimal amount of space in what is already a long post. Google and Facebook do dominate internet advertising and the general trend with respect to concentration in this specific media market is up – as stated above. However, once we scaffold upwards from there to get a sense of how internet advertising fits into the whole media economy, we can see that it accounts for just 5.9% of a total $78 billion in revenue in 2015. Google and Facebook were the 6th and 14th biggest media operators in Canada in 2015, and had estimated Canadian revenues of $2.3 billion and $757.5 million, respectively. They accounted for 3% and 1% of all revenue across the media economy.

By comparison, the biggest player, Bell Canada, had $21 billion in revenue from its telecoms and TV operations in 2015. This was 28% of all revenue across the whole media economy, and nearly twice the size of its largest rivals: Rogers and Telus. It ten times that of Google and more than 25 times the revenue of Facebook. Thus, while certainly impressive, Google and Facebook don’t quite cut the imposing figure that The Shattered Mirror makes them out to be once placed in context.

When we look at specific media sectors and across the media economy as a whole, four observations about concentration levels in Canada stand out:

- They are generally high (with the exception of radio and magazines);

- They have gone up since the turn-of-the-21st Century (except modest dips from still high levels in the past five years for mobile wireless and cable/IPTV TV);

- They are not unusually high by comparative international standards but that’s mostly because, as one of the most authoritative sources on the subject states, media concentration around the world is “astonishingly high” (Noam, 2016, p. 25 and especially chapter 38, pp. 1307-1316);

- Canada is unique, however, in its high levels of vertical and diagonal integration.

In terms of vertical integration, Canada stands unique amongst countries insofar that telecoms operators own all the main television services, except the CBC. The scale of vertical integration more than doubled between 2008 and 2015, as the “big 4” – Bell, Rogers, Shaw (Corus) and QMI – expanded their stakes into mobile wireless, internet access, television distribution and more traditional areas of the media such as TV and radio. The “big 5” television groups – Bell, Shaw (Corus), Rogers, Quebecor and the CBC – collectively owned 217 television services in 2015. They accounted for 86.2% of total television revenue, up from three-quarters in 2008. Their TV operations include Canada’s major TV news outlets, from broadcast TV networks like CTV, Global, CityTV and TVA, as well as cable news outlets such as CTV, BNN, the Canadian franchise for the BBC, CablePulse 24, and so forth. The big four vertically-integrated telecoms giants are central to the news ecology in Canada. The Shattered Mirror gives no sense of this.

Beyond this, there are three other reasons why the unique structure of the media and communications industries in Canada are not peripheral, or anachronistic, but central to the study of news.

Lush Profits, Thin Journalistic Gruel

First, similar to the conditions at Bell that we saw earlier, Shaw, Rogers and Quebecor had operating profits of 42%, 38% and 37%, respectively in 2015 — roughly four times the average for Canadian industry. Shaw’s operating profits for its media division (including Corus, which is jointly-owned and controlled by the Shaw family) of 33% — even higher than those of Bell (25%). Operating profits at Rogers and Quebecor’s media divisions were a more modest 8.3% and 7.3%, respectively – a little lower than the average for Canadian industry. These observations are at odds with the story of doom and gloom that permeates The Shattered Mirror. The situation ranges from ho-hum at the media divisions of Rogers and Quebecor to fantastic at Bell and Shaw. While there is a difference between their focus on television news versus newspapers, which are increasingly ‘sticking to their knitting’, the fact that they are among the top news sources for Canadians furthers the point that they should be at the heart of the matters before us rather than pretty much excluded altogether.

Journalism and Data Caps: Reducing Dependence on the ‘Vampire Squids’ (i.e. Google and Facebook)

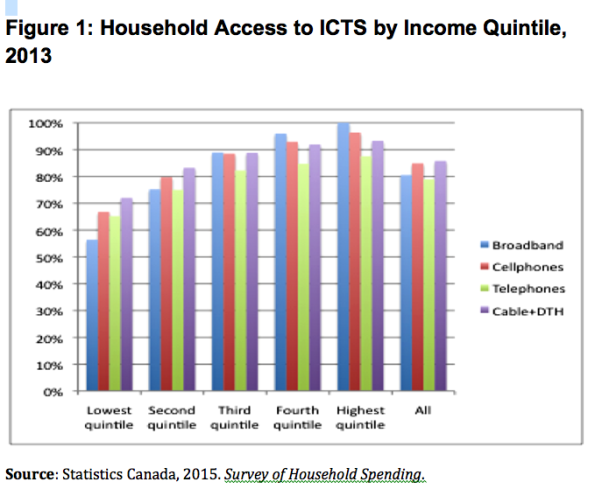

Second, these vertically-integrated companies also own all the main distribution networks (e.g. mobile wireless, wireline, ISPs and BDUs). Consequently, instead of wireline cable and telephone companies competing with wireless companies for control of customers’ access to the internet, TV and beyond, they have dominant stake on both sides: e.g. wireline and wireless. This is known as diagonal integration.

The last stand-alone mobile wireless company in Canada – Wind Mobile – was acquired by Shaw in 2016. By contrast, in many countries there are stand-alone, ‘maverick’ mobile network operators such as T-Mobile or Sprint in the US, or 3 in the UK.

Diagonal integration is important because it dampens competition between rival networks. Where it looms large, subscription prices for internet access and mobile phones tend to be a lot higher, data caps much lower, the application of zero-rating to some content and services but not others is more extensive, and ‘excess use’ charges very steep. Recent studies show that the cost of mobile wireless data plans is very high and data caps low in Canada relative to the EU28 and OECD countries (see Tefficient, 2016, p. 12; Rewheel, 2016, The state of 4G pricing – 1st half 2016 DFMonitor 5th Release).

These structures of ownership and the practices they engender can also transform carriers into editors, or gatekeepers. In doing so, it makes them more like broadcasters and publishers rather than common carriers (an idea that is similar to but not the same as what is now commonly referred to as Net Neutrality). The heavy reliance on relatively low data caps and expensive overage fees by all the telecoms-internet and media giants – Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Quebecor — in Canada constrains what and how people consume the news, watch TV, listen to music, communicate with one another over the internet and mobile devices, buy stuff, consult online health and education resources, and work.

As an integral part of human experience, and the critical infrastructure of the economy, society and journalism, this is an enormous issue. Many of those pushing for a renewed sense of cultural policy have called on the government to leverage these conditions by zero-rating Canadian content (i.e. exempting it from data caps) while applying data caps to everything else. Doing so is an explicit call to gerrymander control over the pipes to tilt the field against ‘foreign content’ in favour of Canadian content. Imagine, however, if data caps were far more generous and prices more affordable. Then, Canadians could freely access content of their choice, including news which, as The Shattered Mirror shows they value greatly (even if unwilling to pay for it), without worrying about going over their restrictive monthly data caps and paying a punishing price because of that.

This would have great value for news organizations as well. They would benefit in two ways. First, news organizations would enjoy a less obstructed pathway to where their audiences increasingly get their news from: their smartphones. Second, they would avoid the non-negligible costs of designing their online news offerings for platforms such as Google’s AMP and Facebook Pages.

Google AMP and the news sites that use it are explicitly designed for mobile wireless access, for example, where the cost of data is high and the use of data caps by mobile wireless operators prevalent and a lot lower than the desktop Internet. Based on this, Google’s AMP strips down webpages and services so that results load nearly ten times as fast, thereby saving on data charges.

The costs of designing for Google AMP, however, are considerable and a whole new sub-industry of designers with specialized technical and journalistic skills is being called into existence to service the need, and charging accordingly. The roster of the ‘big brand’ news organizations that have signed up to these efforts speaks volumes about who can afford the additional burdens, financial, technical, human or otherwise: eg. the CBC, Postmedia, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, Financial Times, Vox, Atlantic.com, to name the most prominent.

At the end of the day, the central question remains: does any of this work? Nobody knows.

Nonetheless, these platforms are fast becoming an integral part of the news ecology, and they are also part of the problem of news providers having to give up control of their content and operations to internet companies. By dealing with the high-levels of vertical and diagonal integration in Canada that are at the root of restrictively low data caps that magnify the cost of uniting audiences with journalism to begin with, the happy upshot could be to lessen journalism’s excessive dependence on the ‘vampire squid’ internet giants like Facebook and Google that the Public Policy report rails against.

Blowing up the Bottom Line: The High (Social) Cost of Media Concentration

Perhaps one of the most important reasons that it is folly to willingly turn a blind eye to high levels of media concentration and the peculiar structure of the media industries in Canada is because the costs of bulking up have had devastating impacts. The cost of bulking up that have led to where we are have not been negligible and were built atop dreamy-eyed visions of convergence from the late-1990s until the turn of the century. At the time, the valuations of media assets soared but such visions of the future failed while saddling media enterprises with unsustainable debt levels that were payable at interest rates that sometimes ran as high as 18% in the case of Canwest, for example. This took place precisely when all-hands-on-deck were needed to deal with the rise of the internet and changing audiences’ behaviour. Many of these ventures failed and wiped out billions in capital. A few highlights will help to illustrate the point.

Sun Media, for example, was acquired by Paul Godfrey at a total value of just under $400 million in 1996, with a few small papers added in exchange for the Financial Post the next year, and then flipped to Quebecor in 1998 for $983 million – double the original value in two years. Quebecor then acquired regional newspaper publisher Osprey for $517 million in 2007. All-in-all, the combined value of Sun and Osprey was nearly $1.5 billion. They were sold back to Godfrey and Postmedia in 2015 for $316 million — $1.2 billion in the value of the capital behind the newspapers wiped out, while onerous debt payments continue to hang like an albatross around the biggest chain of newspapers in the country until the present day.

So, too, with the Southam newspaper chain. Conrad Black consolidated ownership over the chain in 1996 for around $1.2 billion, then sold them to Canwest four years later for $3.2 billion. However, Canwest went bankrupt and the papers were sold to Postmedia in 2010 in a highly leveraged deal for $1.1 billion — the same as when Black gained control decade-and-a-half earlier. Last year, Postmedia was worth $56 million — a loss of a billion dollars in market capitalization in five years (also see Bruce Livesey’s National Observer article and Marc Edge’s new book on the meltdown of journalism within the Postmedia empire, and more broadly).

At the height of the turn-of-the-21st Century convergence craze, Bell acquired CTV and the Globe and Mail. Together with the Thomson family it created Bell Globemedia, with Bell holding a 70% ownership stake in the entity and the Thomson family the rest. The capitalization of the new company was $4 billion. Bell Globemedia floundered from the beginning, however, and Bell exited the business in 2006. The venture was renamed CTV Globemedia and recapitalized at a value of $1.2 billion – a loss of nearly $3 billion (BCE AR 2006, p. 84). Of course, Bell reacquiring CTV in 2011 for $1.3 billion.

Collectively, roughly $6 billion in market capitalization was destroyed and precisely when the country’s biggest media companies should have been focusing attention, investment and whatever other resources they could muster on dealing with the rise of the internet and, somewhat later, the smartphone, and changes in how people were using the media. This is to say nothing of the extraordinary wave of lay-offs and job cuts at these outlets, and the labour strife that accompanied such processes. The Public Policy Forum’s report gives us a whiff of the costs in terms of journalistic and editorial jobs lost, but nowhere does it connect the dots. Of course, having ruled these issues “off-limits”, what should we expect?

Inner Circles, Cloistered Views and Missed Opportunities

That The Shattered Mirror, as it’s lead author’s post release comments indicate, willingly walked away from these issues is stunning, and naïve. In doing so, it walks away from an impressive body of research from around the world that says that these issues are important, extraordinarily complex, and foundational to understanding the emerging digital media environment.

While I am happy that the authors plucked from some of our flagship reports (see here and here), I am disappointed that they only picked the juicy parts that fit into their vilification of Facebook and Google and the “vampire economics” that they say rules the highly concentrated internet advertising market in Canada while turning a blind-eye to all the other data and discussion in our report. Interested readers will also find much value in the work Eli Noam, a Professor of Finance and Economics at Columbia University and editor, most recently, of Who Owns the World’s Media, a thirty-country survey done by as many research teams covering three decades that looks at the issues in front of us with an open mind, and some stunningly important conclusions – many of which are counter-intuitive and at times seems to run at cross-purposes to one another. Robert Picard of the Reuters Institute of Journalism at Oxford University is another excellent media economist who looks at these issues with an open mind, as is Gillian Doyle, among many others.

That the report refuses to engage with media concentration and the peculiar structure of the media is not surprising given that many of those surrounding its lead author, Edward Greenspon, in the development of this report have not just sat back and taken arm chair academic views on these matters but have been leading cheerleaders for the processes of consolidation in Canada that have got us to where we are. So why look in the mirror? The industrious reader can consult the list of acknowledgements to sort out who is who and draw their own conclusions.

Given all this, that media concentration wasn’t on the agenda is not surprising. It’s still a pity, though, because the issues are serious. By taking the course that it has, the report has also squandered an opportunity to build on the momentum that has been building in regulatory circles at the CRTC, Industry Canada and even the Competition Bureau. For the past several years, each of them have been using many of the policy levers at their disposal to address media concentration and counter some of the abuses of dominant market power present in several media markets – abuses that are no longer mere allegations but established legal facts. That the Public Policy Forum has taken the stance it has is a missed opportunity, not just in terms of building on the momentum that already exists amongst regulators and policy makers, but also the incredible amount of research and writing that many scholars, public interest and consumer groups, citizens and others have poured into these activities.

Final Thoughts and a Few Policy Proposals

The effort fails in terms of the analysis conducted for all the reasons set out above, and because the prescriptions counselled draw from the past and will be a drag on the future. Its analysis fixates on a dwindling part of the media, namely media that are subsidized by advertising, as if they are a part of the natural order of things and should be so forever. As both an empirical and a normative matter, this is simply not the case.

In the real world, however and as we have seen, the media economy is increasingly internet- and mobile wireless centric. For better or worse, subscriber fees and the “pay-per model” have become the driving force. The report fails to deal squarely with the idea that the underlying subsidy that has been provided by advertising for a good part of the 20th Century is stagnating, and by some measures in decline (per capita), and that the part of the advertising revenue that does remain is going to Facebook and Google not because they are venal but because they are more efficient at doing what the ‘legacy media’ used to do best: deliver audiences to advertisers.

That was always a bit of a Faustian bargain, and still is. There is no reason why we should pull out all the stops to try to bring it back. It won’t happen, and advertising subsidized media raise their own prickly problems, not least of which is it is never really the audience – us – that are the main parties calling the shots. Given the extent to which it is wedded to advertising, it is also not surprising that the report acknowledges but shies away from another undeniable fact that is inseparable from the points raised here and which is key to understanding journalism: the general public has never paid for a general news service. This has not changed (see here and here, for example).

Forgetting also that there has never been any true love between business and the advertising-supported media model — just a marriage of convenience — the report keeps alive the innocent fable of how the mutually beneficial relationship between advertisers, journalism and audience brought us “the free press” and how we must wrestle this back from the “vampire economics” of Silicon Valley. No, that won’t work, no matter how much the report gooses the numbers and argues in favour of its proposal to impose a withholding tax on the advertising and subscriber fees of ‘foreign digital platforms’. Nor should it. The invidious distinctions between Canadian media versus those from the world beyond our borders that it draws is based on warmed over cultural nationalism from the 1960s and 1970s, and this, too, should also raise an eyebrow.

The idea that we should harness society’s whole communication infrastructure – increasingly the internet – to foster a small sliver of activities that people use it for is also backwards. As said earlier, in the past, this may have been an acceptable idea because a limited purpose broadcasting distribution network was leveraged to support a single activity: broadcasting. Means were directly related to ends, and this made sense, even against the tough standards of free speech. Yet, today, we are in a different place where Canadians are being asked – incessantly – to harness a multi-purpose and general communication infrastructure (the internet) that already supports a vast array of activities that continue to expand in terms of diversity to a narrow, albeit incredibly important, range of activities.

The Shattered Mirror is not a forward looking report in these regards. It largely ignores questions about how the availability and control of distribution infrastructure (rather than just “digital platforms”) fundamentally effects the shape of the news media overall. To the extent that it does, the recommendations trot out the familiar calls for an ‘ISP tax’ to fund journalism that is so beloved by resurgent cultural nationalist groups (rather than the capacious language of “general intelligence” and “the people’s correspondence” that informed the universal postal system during the founding days of American democracy). They seem to see Minister Joly’s review of Canadian Content in the Digital Age as a once in a lifetime chance to entrench policy tools designed a half-a-century ago for ‘the industrial media age’ forever by applying them holus bolus to the emergent internet and mobile wireless-centric communications and media universe of the 21st Century. Nothing could be less helpful.

As I have tried to make clear above and every time I write on these matters, I am an enthusiastic supporter of the idea that a viable democracy needs good journalism, and that the culture of a democratic society needs arts, knowledge, media, public libraries, schools, science, archives, and a whole bunch of other things. We need a big view of culture, and we need to pay for it accordingly. So here are a few of my big ideas:

- Bite the bullet and accept that the general public has never paid full freight for a general news service and that, consequently, it has always been subsidized by advertising, “the state” or rich patrons. The question is how to do that today in a way that is fair, independent, effective, and accountable? The report goes part way in this direction with its Policy Recommendation #3 to change tax laws to encourage charities and philanthropists to step into the breach and invest in original news. I agree, but also think we need to dig deeper along the lines suggested below.

- Apply the HST/GST to all advertising expenses and subscription fees without discrimination based on medium or nationality, and earmark the funds generated for a “Future of Journalism and Democracy Fund” of the type the Public Policy Forum envisions (Policy Recommendation #5), but make the fund even broader to support other kinds of original Canadian content creation, from films, TV drama, video games, music, archives, etc. Consolidate the CanCon funds I say, and take a very big view of what CanCon is.

- Bolster the CBC across its mandate to inform, enlighten and entertain versus The Shattered Mirror’s emphasis on the first function (its Policy Recommendation #10). Do this because a ‘platform agnostic’ public media service not only informs people but plays a key role in cultivating new talent across the arts, and exposing artists to the audiences they need to go on to become bigger commercial successes. In line with these ideas, unshackle the CBC from any suggestion that its sails have been forever tied to the listing mast of the broadcasting ship. It should also be funded accordingly and in line with median levels of government support for public media in OECD countries (versus at the lower ends of the scale) (a modified version of the Public Policy Forum’s Recommendations 11 and 12, but without the restrictive focus on the CBC’s “informing” function).

- We can no longer think about journalism and the media without thinking about broadband internet and mobile wireless. In an ever more internet- and mobile wireless-centric media universe, this is essential. The “founding fathers” in the US stressed the essential role of a free press to democracy (as The Shattered Mirror notes), but they also went much further by subsidizing a universal postal system to bring “general intelligence to every man’s [sic] doorstep” to the tune of tens of billions of (current) dollars a year in the 19th Century to achieve that aim. So, too, must we integrate our thinking about broadband and mobile wireless policy with content, journalism and news together today (on postal history and news, see John).

- This means emphasizing the importance of common carriage and universal broadband internet. It is essential to not impose the publishing or broadcasting models on society’s communication infrastructure. Mobile wireless and internet access providers should be gateways not gatekeepers. This will help ensure that news organizations and all forms of media, cultural and personal expression can have unfettered access to those with whom they’d like to share an experience, an idea, a story. It will also help to reduce journalists and news organizations from their growing dependence on Google, Facebook, Apple, etc. for the reasons outlined above. Universal broadband internet service should also be funded accordingly by raising the subsidy from its current level of roughly $2 per person per year to a figure, by way of suggestion, between the $5 per person per year that Sweden invests to promote universal broadband internet uptake and the $33 per person per year that we currently invest in the CBC. The report is silent on these issues but by implication, it is hostile to them.

- Crush the idea that appears from time-to-time in the report that Facebook and Google should be treated like publishers. They are not. Similar to how the development of modern capitalism depended on the creation of the limited liability corporation so too do broadband internet and digital platforms that host, store and distribute huge amounts of other people’s content require the concept of the limited liability ‘digital intermediary’ to operate at scale. Google, Facebook, and the others that facilitate commercial and cultural intercourse over the internet are already treated this way by the law, and they should continue to be treated as such, without being ‘above the law’, or worse enrolled by governments using beyond the rule-of-law tactics to tackle a myriad of evils, whether stamping out child pornography, mass piracy, terrorist propaganda, counterfeit goods, etc. Where the interest is great, the law needs to swing in behind the power that these intermediaries have by dint of the fact that they stand mid-stream amidst the torrent of internet traffic.

The fact that intermediaries are increasingly being enrolled by governments to undertake these tasks without proper legal underpinnings, however, has already created problems enough (here, here and here). Calling, as this report does, to enroll ‘digital intermediaries’ like Facebook and Google to suppress “Fake News” is similarly fraught with problems. That this is so is readily evident in Facebook’s ham-fisted approach to enforcing its “community standards” that have led it to censor, for example, the Pulitzer Prize winning “napalm girl” photo of Kim Phuc running naked away from a village just after it was bombed by the US during the Vietnam War and when it has taken down or otherwise blocked access to images of, for instance, the famed Statue of Neptune in Bologna, the Little Mermaid Statue in Copenhagen, Evelyne Axell’s Ice Cream and Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World. Illma Gore’s sketch of Donald Trump in the nude has also been banned from the site (see here).

While the desire to stamp out ‘fake news’ may seem especially appealing at the moment, there is good evidence that despite the fact that “fake news stories” were plentiful in the 2016 US election, the effects are probably not as strong as many seem to think. As the new “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election” study by Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow from New York University and Stanford University, respectively, finds, this is because even though Americans use social media a lot, only a small portion of them – 14% — relied on social media as their “most important source of news” during the election. Instead, TV was the main source of political news by far. Even those who did get their news from social media, and were therefore exposed to fake news that favoured Trump over Clinton by a wide margin, very few could remember “the specifics of the stories and fewer still believed them”, observes a Poynter Institute summary and commentary on the study being recited here.

Ultimately, we need to see this report for what it is: the latest in an unending firehose of reports from well-heeled think tanks across the country, including the Friends of Canadian Broadcasting (here, here, here), the Fraser Institute, the MacDonald Laurier Institute and the C.D. Howe Institute that cover much the same ground. All of them respond to and in one way or another try to influence Heritage Minister Melanie Joly’s call for a top-to-bottom review of cultural policy, dubbed Canadian Content in a Digital World. That she has stimulated such interest is to her credit. However, the extent to which these reports are flooding the ‘marketplace of ideas’ with tired old ideas is a problem that I hope she and the good folks at the Department of Canadian Heritage – the cultural policy sausage factory, if you will – recognize them for what they are, and deal with them accordingly.

The Shattered Mirror also complements the Canadian Heritage Parliamentary Committee’s unfinished survey of similar terrain, and a series of recent decisions by the CRTC that are intended to shape the future of TV, broadband internet and mobile wireless services in this country: (1) its trilogy of Talk TV decisions; (2) its universal broadband internet service, and (3) several others that go to the core of the increasingly fibre and mobile wireless internet infrastructure that underpin the entire communications and media landscape upon which more and more of our economy, society and our day-to-day lives depend.

This report has nothing to say on the full sweep or specific details of these matters but lines up with those complaining bitterly about the CRTC’s new found willingness to take on media concentration and the perils of vertical and diagonal integration. The extent to which they do so and pine to keep industrial-era media policies — tweaked to bring them up to ‘digital speed’ — forever is a measure of how backwards such stances are and really just how much they see things through a rearview mirror. We deserve better, and let’s hope we get it.

Why Bell’s Bid to Buy MTS is Bad News

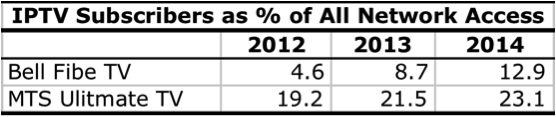

Last week, BCE announced its $3.9 billion bid to acquire MTS, the incumbent wireless, internet and IPTV provider in Manitoba. BCE’s share of revenue (28%) across the telecoms-internet and media landscape is already close to double that of Rogers (16.3% market share) and Telus (15.9%). Approving this deal would only further gird Bell’s place at the apex of the Canadian communication system.

Blessing the deal would also be at cross-purposes with findings by the CRTC and Competition Bureau on several occasions last year that telecoms and TV markets in Canada are highly concentrated, while turning a blind eye to the anti-competitive behaviour that led to those findings. The number of mobile wireless competitors in Manitoba would also drop from four to three as a result, effectively putting a stake through the last government’s policy of promoting four wireless carriers across the country.

Of course, there is no need for the new Liberal Government to keep a policy created by its predecessor, but it would be well-advised to consider the real benefits of keeping this policy (see the OECD’s review for why this is so). Finally, and this is key to the analysis that follows, what if, contrary to the claims of the deal’s backers, MTS has maintained low prices while achieving profit levels and making substantial capital investment in 4G mobile wireless, fibre-to-the-doorstep and competitive TV services?

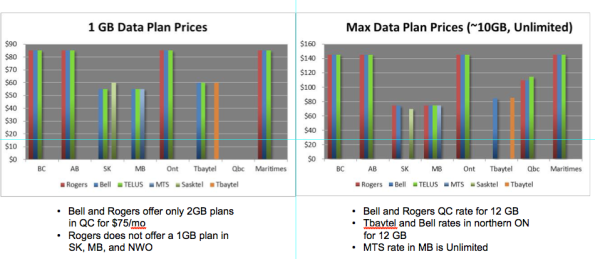

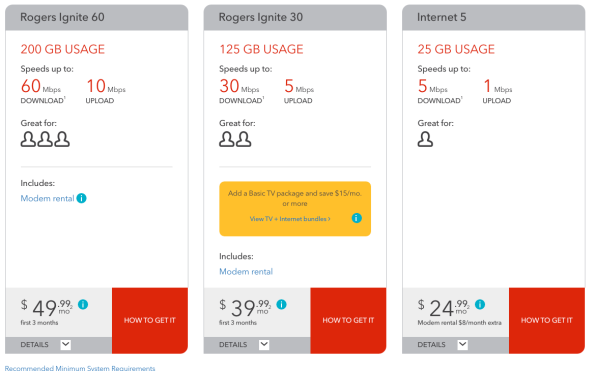

Do Low Prices Amount to a Short-Sighted Race to the Bottom and Low Quality Network Infrastructures?

So far several commentators have raised the alarm that a takeover of MTS will drive up prices as Bell, Rogers and Telus assert their dominance in Manitoba in a manner all to familiar to other regions across the country (Geist and Blackwell). Such a prospect turns on the fact that already Bell, Rogers and Telus price their plans $30 to $70 less than their equivalent offerings in Ontario, Alberta and BC to meet the rates charged by MTS and SaskTel in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, respectively. Figure 1 below illustrates the point.

Figure 1 Retail Wireless Plan Prices by Province (September 2014).

Source: MTS, SaskTel & tbaytel (2015). Telecom Notice of Consultation CRTC 2014-76 Review of Wholesale Mobile Wireless Services (para 25).

According to Bell and MTS, however, the deal is not about maintaining cheap but lower quality services at all. Instead, it is about bringing MTS out of the dark ages and into the future with an ambitious billion dollar investment program spread over five years to bring state-of-the-art fibre optic networks in Manitoba, increase the reach of Bell’s “world class” Fibe TV service, and to expand wireless 4G LTE network coverage in the province (BCE, Analyst Presentation, 2016, p. 6).

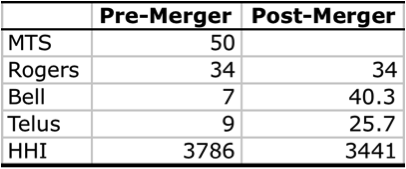

BCE’s CEO George Cope has been keen to emphasize that the market might become even more competitive after the deal. As he sees it, there will be three large firms competing even more aggressively after the deal than the current situation where MTS rules the wireless market with over half of all subscribers followed by Rogers with a third of the market share, trailed far behind by Telus (9%) and Bell (7%) (based on 2014 figures) (CRTC, 2014, unpublished data; also MTS, 2014 Ann Rpt, p. 7).

The intensification of “sustainable competition” would be especially likely, it is claimed, after Bell divests one-third of MTS’s wireless subscribers to Telus, as the deal envisions, according to Cope. The upshot is that instead of two strong competitors, MTS and Rogers, followed in the distance by Telus and Bell, there will be three “strong players”. Table 1 below shows the pre- and post-merger results.

Table 1: Mobile Wireless Carriers’ Market Shares in Manitoba Pre- and Post-Merger

Source: MTS (2015). Annual Report 2014, p. 7.

According to this view, this is how dynamic competition works. Big players with deep pockets, staying power and know-how compete vigorously with one another on the frontiers of technological and service innovation rather than on the basis of “unsustainable price rivalry”. Regulatory economist Gerry Wall also chimed in to support this line of argument, telling the National Post that while MTS wireless pricing “forced the Big Three to match [its] low prices”, such a strategy is “unsustainable”. As Wall further added:

The aggressive pricing strategy has been successful in terms of keeping customers but I think it has taxed them financially – and the investment required for 4G and next gen networks is very challenging (quoted in Corcoron, 2016, “Good Riddance to Fourth Carriers”).

In simple terms, to focus on cheap prices now might sell Manitobans down the river in the long-run if MTS is not making enough money to build the infrastructure needed to support the province in the 21st Century. These are serious issues indeed, but are they right?

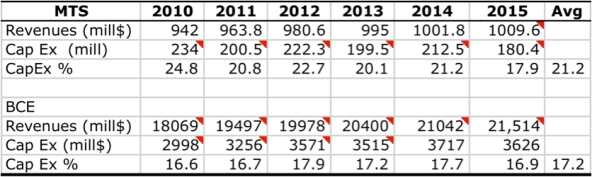

I don’t think so. In fact, as we will see below, while prices are low in Manitoba compared to much of the rest of the country, profits and capital investment at MTS are actually higher than Bell’s.

Why Even Imperfect Competition is Better than a Tight Oligopoly

BCE’s bid for MTS must obtain the blessing of three regulators: Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED, the recently renamed Industry Canada), the Competition Bureau and the CRTC. One of BCE’s main claims in favour of the deal is that it holds forth the prospect for sustainable competition if given the green light by regulators. Seeming to recognize that this is not a slam dunk, BCE and MTS expect the review process to take up to a year.

On the basis of the standard tools typically used to examine these things – i.e. Concentration Ratios (CR) and the Herfindhahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) – the case is doubtful. In terms of the CR measure, we will go from a situation where the top four firms control 100% of the market to one where three firms will do so.

While the distribution of market shares of Bell (40%), Rogers (34%) and Telus (26%) (see Table 1 above) that will result should the deal be approved does tally with Bell’s view of things, the HHI – which is specifically designed to assess competitive intensity – tells a different story. The HHI score will decline from 3786 to 3441, but the more urgent point is that this still indicates skyhigh concentration levels. Indeed, any result over 2,500 indicates extremely high levels of market concentration. This deal will do nothing to change that.

Even these points underplay the extent to which consolidation dynamics will likely be ramified by BCE’s takeover of MTS. For instance, while Bell presents its plan to divest a third of MTS subscribers to Telus as a magnanimous gesture intended to mollify regulators, this ignores the fact that the two have had a network sharing deal that covers the province since 2001 (see Klass, 2015).

Furthermore, Bell’s takeover of MTS could leave Rogers out in the cold given that it and MTS have paralleled Bell and Telus to build jointly-shared networks of their own. MTS and Rogers first joined forces in 2009, for instance, to build a shared HSPA+ mobile wireless network in Manitoba. Similar arrangements were struck again in 2013 to build a shared LTE network; in fact, before the takeover was announced, MTS already had plans in place to cover more than 90 per-cent of Manitoba’s population with 4G LTE wireless service by 2018 (MTS, 2013 AR, p. 12).

Where Rogers will stand once that agreement comes to an end, however, has so far gone unspoken. If Rogers is left out in the cold, then the circumstances will be worse than ever, with not even a full duopoly left, given Bell and Telus’ shared interests in the province. However, even if Rogers is taken care of, so to speak, the cozy oligopoly that now straddles much of the land will only be reinforced.

That already very high levels of concentration exist and could get worse is not a mystery. As Eli Noam (2013) observes, concentration levels around the world for these markets tend to be “astonishingly high” (p. 8).

What has made the difference is regulators willing to face up to such realities and deal with them accordingly. And a key element in such responses has been the adoption of fourth wireless carrier policies. Of course, there is no magic number in terms of how many players a market can sustain but experience shows that a fourth competitor helps to break dominant players’ tendency to fly as a flock in markets defined by a tight oligopoly.

The advent of four or more rivals, in turn, results in more competitive retail pricing as well as more robust wholesale access regimes and a virtuous circle of more competitors, greater pricing diversity and the advent of mobile virtual network operators, for instance – all of which helps to breakdown barriers to adoption. This is especially important in Canada with respect to mobile wireless services, where it ranks 32nd out of 40 OECD and EU countries (see Broadband Wireless Penetration sheet)

Moreover, the pursuit of the “fourth competitor” policy is far from being just a populist ploy, as some critics grouse. Indeed, with communication costs a key part of doing business within Canada and around the world, businesses are pushing for lower wireless and broadband internet prices. This is why such issues are pressing more urgently not just on Canadian policy-makers and regulators but also their international counterparts at the OECD and WTO as well (OECD, 2013, p. 21).

Profits @ MTS are High, Not Low

Claims that competition and low prices have been artificially sustained in Manitoba collide with the reality that profits at MTS are very high, not low, and much higher than BCE’s actually. Bell itself noted the point in its presentation to analysts, suggesting that MTS EBITDA rates were comparable to its own, i.e. in the 40% range (BCE, Analyst Presentation, 2016, p. 5).