Archive

Telus Trifles with Telephone History to Service its Constrained View of Universal, Affordable Broadband Internet Access Today

Setting the Stage

Today, the CRTC enters week two of its major review of affordable basic telecoms service in Canada. The key issue? Whether universal, affordable basic telecoms services should be expanded to include broadband internet access and, if so, at what standards of speed, quality and affordability, and who should pay for it all.

Some of us argue that the goal of affordable, universal broadband service needs to be defined broadly. Others, such as Telus, argue that it should be drawn very narrowly to include only services based on needs not wants. In Telus’ restrictive view of the world, basic broadband internet access should support email, web browsing and maybe a couple of e-commerce activities but not over-the-top video services or H-D two-way interactive gaming. If the CRTC is to adopt a broadband speed target at all, Telus says, it should be no more the 5 Mbps down, 1 Mbps up (see its second intervention, paras 90-91).

To support its view, Telus hired two experts to critique the work submitted by those who argue for the more expansive view, including that of your’s truly. The gist of my submission is that affordable universal service is a concept that is not static but changes with developments in technology and society. I also argue that the politics of universal service involved in working this out are coterminous with the history of general purpose communications networks from the post office to the telephone and now the internet.

In the US, for example, this began with the post office starting with the Postal Act of 1792, and whose mandate was “to bring general intelligence to every man’s [sic] doorstep”, while also serving as a heavily subsidized vehicle for delivering newspapers across the country with the aim of helping the nation’s journalism flourish (John, 2010, p. 20; Starr, 2004). In short, universal postal policy was also about press, information, social and economic policy, all rolled into one.

I then argue that people agitated for such goals in relation to POTs (plain old telephone service), libraries and broadcasting. That they are doing so now in relation to broadband internet access is no surprise.

Indeed, in Canada and the US people pushed hard to transform the telephone from the late-19th and early 20th centuries from a luxury good and tool of business and government into a social necessity (Pike & Mosco, 1986), and a popular means of interpersonal communication. In an all-IP world, people are building upon this history by not only bringing intelligence to every citizens’ doorstep but by helping to make that doorstep the perch from which we can see and speak to the world.

Hired Guns, Weird Timeframes and Looking for Keys Under Lampposts

In line with Telus constrained view of basic service, its hired expert, McGill Political Scientist Richard Schultz writes that we need to clear away the many misconceptions and myths that exist about how “universal service became part of Canadian regulatory and policy debates” (para 2). Taking aim at my intervention specifically, Schultz asserts that

. . . perhaps no single statement in the various submissions epitomizes the problems . . . than the following from the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project first intervention: “Policy makers have struggled for over 100 years how best to achieve universal telecommunications service” (para 4).

Purporting to set the historical record right, Schultz argues that we need to do two things: first, to look at the period “from 1906, or more precisely 1912” up to around 1976, followed by another thereafter” and, second, search for explicit statutory statements where universal basic service is set out as a formal legal requirement for basic service, with the assumption being that the absence of such statements means that there’s never been such an idea in Canada and that claims to the contrary are just hollow rhetoric.

After doing what is akin to a text search of the relevant laws and coming up empty handed, Schultz concludes that there never were such politics over, or legal basis for, universal service in the late-19th or early-20th centuries and, in fact, that such issues were largely ignored. To the extent that such issues were given attention at all, he argues, the impetus came from enlightened corporate leaders at Bell and other telephone companies rather than politicians, policy makers or the public at large – in other words to the extent that universal service existed at all, it was an act of noblesse oblige (paras 5-9). Moreover, according to Schultz’s telling, to the extent the regulators and policy makers have played a role in bringing it about, universal service is of recent vintage.

Shultz’s arguments are curious for two reasons. First, the date that he begins with ignores vitally important points that predate 1906, while ignoring or giving short shrift to events within his selective timeframe. Second, the idea that a text search for “universal service” in the relevant legislation that comes up empty handed supports the conclusion that the idea was non-existent is like the proverbial drunk looking for their keys under the lamp post.

History Cut Short: Looking Just Outside the Weird Timeframe . . .

Let’s deal with the start date that Schultz selects first, i.e. 1906. This date is plausible because this is when telephone companies were brought under the remit of the Railway Act of 1903 and the purview of the first regulatory board in Canada, the Board of Railway Commissioners. Yet, starting in 1906 is fundamentally wrong for many reasons. For one, if we start just a few years earlier, we see that the adoption of the Railway Act was predicated on the idea that there are certain industries so fundamental to the economic and social life of the nation that they are imbued with a public interest and an “obligation to serve”. Railways came first, telegraphs and telephones next.

Statements aplenty to this effect underpin the legislative history of the Railway Act, and when telegraph and telephone companies were brought under its purview three years after its adoption the same principles automatically applied. Thus, when the Railway Act was expanded to include telephones in 1906, there was no need to be explicit about the “obligation to service” because that was baked into the statutory basis upon which railway, telegraph and telephone regulation was based. In short, there was no need to state the obvious.

The classic text on such matters, Alfred Kahn’s The Economics of Regulation: Principles and Institutions, provides an excellent introduction to businesses cloaked with a public interest, their obligation to serve, and the role regulators play in using the best available knowledge and experience to decide how such matters will be dealt within in any particular instance (see pp. 3-5, for example). These are the guiding rules and principles of regulation, not legislation, although regulators’ authority to do what they do is and must be grounded in laws that give them the authority, mandate and legitimacy to take the steps they do.

Schultz’s start date of 1906 is especially odd given the monumental inquiry into the telephone industry convened just one year earlier – 1905 — by the Liberal Government of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, otherwise known as the Mulock Committee, after its chairperson and Postmaster General at the time William Mulock. The Mulock Committee helps to put the CRTC’s review of the basic service obligation in perspective given that while the Commission will hear from 90+ intervenors over three weeks, the Mulock Committee heard from many more during its forty-three days of hearings and thousands of pages of testimony.

As part of the public record, it received interventions from members of the public, co-operatively run telephone companies, municipal governments, foreign telephone systems and experts, and Bell management, among many others. It was an enormous undertaking, and one that underscored the fact that achieving some measure of public control – i.e. regulation in the public interest — over the telephone network was of the utmost importance.

Contra Schultz and Telus’ claim that issues of universal service were missing in action during this early period of telecommunications history, voices aplenty called for accessible and affordable telephone service at this time, not just for the business classes who were its main users but for all classes of the public. One among many, the Manitoba Government’s submission, for example, highlighted these points as follows:

. . . the telephone is . . . one of the natural monopolies, and yet is one of the most . . . necessary facilities for the despatch of business and for the convenience of the people . . . .[T]he price . . . should be so low that labouring men and artisans can have convenience and advantage of the telephone, as well as the merchant, the professional man and the gentleman of wealth and leisure” (Manitoba Government to Mulock Committee in 1905, quoted in Winseck, 1998, p. 137).

If this is not a call for affordable service, I am not sure what is. The only reason they are missing for Schultz and Telus is because such activities fall outside of their self-selected – and odd — time frame that begins a year after the biggest inquiry into the telephone and public service in the 20th Century occurred (except maybe the proceedings dealing with the introduction of competition in the last twenty-five years of that century).

We can also go well beyond 1906 and the Railway Act, or 1905 and the Mulock Telephone Inquiry, to the first days of the Bell Telephone Company of Canada’s operations to add further insight into the history of universal telecoms service. Thus, in 1882, Bell’s founding charter was revised to include the touchstone phrase that its operations were to be conducted and overseen by the federal government for “the general advantage of Canada”.

A few years later, and a decade before the United States pursued the same course of action, the federal Patent Commissioner voided Bell patents because Bell was not making enough use of its equipment in Canada and blocking access to those who might (see MacDougall, 2013, p. 43). Municipalities also chafed — and told the Mulock Committee as much – at how their weak powers under the federal government’s authority and the “general advantage of Canada” idea in Bell’s charter constrained their capacity to grant competing franchises, regulate rates and adopt other methods that might help extend the telephone beyond a small number of business users to make it more accessible and affordable.

And when competition did break out, as in Montreal in 1888, for instance, Bell launched a ruthless price war with its rival, the Federal Telephone Company, until the latter capitulated and sold out to Bell three years later. In Winnipeg it created a “dummy company”, the People’s Telephone Company, to give the illusion of competition; while in Peterborough and Dundas, to kill new independent telephone companies, Bell gave away service for free. Yet, all this, too, is ruled out by the self-selected time frame that Schultz imposes on the subject.

When Kingston joined the Ontario Municipal Association in 1903 to adopt a resolution calling for municipal authority to regulate telephone rates, Bell threatened not to renew its franchise and to withhold further capital investment. In the same year, the Mayors of the Montreal suburb of Westmount and Toronto, William Lighthall and Oliver Howland, respectively, spearheaded a drive to gain greater regulatory authority over telephone rates for municipalities while calling on the federal government to take control of the long distance network. By 1905, 195 municipalities had joined the call, with support from the Montreal and Toronto business associations and the farmers’ association, Dominion Grange (also see MacDougall, 2013, pp. 44-46, 125-127; Winseck, 1998).

In an immediate sense, the cities’ calls largely fell on deaf ears at the federal government. As a result of this drift of events, in 1902, 1-in-50 Ottawa citizens had regular telephone service. The upshot, as Bell Canada President Charles Fleetford Side never missed a chance to stress, was that the telephone was treated as a luxury not necessity.

It was against this backdrop, however, that Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal Government convened the Select Committee on Telephones in 1905. However, none of this even merits a mention in the hired expert report that Professor Schultz has prepared for Telus and submitted to the public record of the CRTC’s current review of basic telecoms service. In short, those parts of the historical record that don’t fit Telus’ restrictive view of universal telecoms service are simply omitted from Schultz’s account.

Inside the Timeframe Things Disappear

Missing, also, is the fact that all three prairie governments effectively nationalized their telephone systems between 1906 and 1909 largely because, as Manitoba had told the Mulock Committee, Bell refused to extend its network in the province or to make the service more affordable for more people. During this time, Bell vacated the field as prairie governments took over telephone service between 1906-1909 in Manitoba and Alberta, although with Saskatchewan following the ‘Scandinavian’ model whereby the government initially owned the long distance networks while cities and cooperatives built up the local networks (MacDougall, 2014, p. 190).

In addition, far from the folding of telegraph and telephone companies into the purview of the Railway Act being an inconsequential gesture, as Telus and Schultz suggest, Canada’s first regulator – the Board of Railway Commissioners — cut its teeth on a wide variety of issues that all had to do with carving out what it means to set public policy and regulate businesses affected with a public interest, to use Alfred Kahn’s terminology. Thus, and for instance, even though some people suspected that the Government had simply shelved the recommendations of the Mulock Committee, the report helped to set the zeitgeist and in the next few years the BRC found its footing on ground made solid by the extensive proceedings that had just transpired.

Thus, between 1908 and 1915, the BRC displayed the will and room for independent action needed to increase the availability of affordable telephone service to business and all classes of people alike. For instance, the BRC nullified the then widespread exclusive contracts that Bell had hitherto sewn up with railway stations – the main centers of commerce and the flow of people – across the country. The provisions in the Railway Act requiring telephone rates that were “just and reasonable” were also given new life; as were those that required that rates and services be offered in a manner that was “not unjustly discriminatory or unduly preferential” (Railway Act, c. R-2).

Standard technical interfaces allowing interconnection between Bell and independent telephone companies were adopted, and telephone companies were required to file their tariffs with the BRC. In 1910, the BRC made a landmark ruling that brought common carriage into the purview of telecommunications in Canada as well, and which remains a defining pillar of the Telecommunications Act (sec 36) to this date.

The BRC also began systematically collecting data on Bell and other telephone companies with respect to rates, miles of telephone line and the number of exchanges in operation, people served, workers employed, and so on and so forth. The first monitoring reports, Telephone Statistics, were published. The number of independent telephone companies soared from 530 in 1912 to 1700 by 1917, accounting for half of all subscribers at the time. To be sure, the exact phrase “universal service” may not appear in these efforts, and the aims of such an objective were not achieved, but its spirit – in bits and pieces and the totality of the record – is undeniable.

To be sure, while Bell struck a tone then that was as parsimonious as the one Telus is striking now, it was not completely tone deaf to the drift of events taking place. Thus, while the Bell Telephone Company of Canada’s long-standing chair, Charles Fleetford Sise was renowned for his penny-pinching ways and emphasis on serving only high-end business users who appreciated the high quality of the company’s networks and didn’t mind paying the price to do so, by 1912 even he seemed to be changing his tune.

Thus, in Bell Canada’s Annual Report of that year, Sise is quoted as follows:

. . . In 1906 the operation of the Company was placed under the supervision of the Railway Commission, which has considered several matters brought before it for adjudication, and has, in its conclusions, acted in an impartial and judicial manner.

Our relations with the Public continue to be very satisfactory, and the general feeling now seems to be that the telephone service to be perfect must be universal, intercommunicating, interdependent, under one control…and that rates must be so adjusted as to make it possible for everyone to be connected who will add to the value of the system to others (emphasis added, Fetherstonhaugh, 1944, pp. 224-225).

This is hugely important because, in Schultz’ words, to the extent that we had universal service at all, it was because the companies gave it to us out of the goodness of their hearts. Yet, here is Sise saying something very different, and in his account, the regulator looms large.

Schultz also draws on Milton Mueller’s (1998) history of universal service in the US to argue that the concept of universal service didn’t really mean what we think it means, but rather was more of a technical concept that referred to a single system (i.e. a monopoly) available everywhere rather than to everyone at affordable rates (see paras 30-31 in Schultz). Again, Sise’s words suggest something different.

The Politics of Telecoms Policy and Universal Service Restored

While Sise was likely singing from the same hymn sheet as the American Bell, the reading that Schultz tries to impose is at odd with a broader reading of Bell and its management’s stance within the context of the politics of the progressive era in the US (circa 1890-1920) when people like AT&T boss Theodore N. Vail worked harder than ever to reconcile a nascent kind of big business capitalism that his company represented, large technical systems of which the telephone system was an example par excellence, and the public interest (see Sklar, 1988, for example). All of these ideas were at play and expressed from a wide variety of positions, from the narrow and technocratic (Walter Lippmann, for example), to the broad and expansive (John Dewey). Even on the face of it, Sise’s invocation of a telephone service that is universally available at rates that “make it possible for everyone to be connected” chime with such views while also resonating strongly with our modern conceptions of universal service.

Suffice it to say that Schultz’s fundamentally flawed account of the history of universal service carries on throughout the period he covers. To be sure, there are times, for example in the post WWII era in which the politics of telecommunications and universal service did fade into the woodwork, but that, I would argue, is due to the “corporatist politics” and social settlements of the era. This meant that such matters were attended by those directly involved: the telephone companies, the regulators, and to an extent the telephone company labour unions. Indeed, when telephone regulation rested with the Board of Transport Commissioners (1938-1967) and then the Canadian Transport Commission (1967-1976), respectively, they did take a particularly technocratic and narrow view of things whereby, rather than hearing from people directly, they believed that the company engineers and economists appearing before them were best placed to deliver insights and results that were in the public interest.

The Public Returns and the Public Interest is Revived

That kind of thinking was also prevalent in the US at the time, as well. Crucially, however, it was also rejected in the landmark United Church of Christ case in 1966 when the Courts scolded the FCC into a new way of thinking by arguing that the only way to know what the public interest is, was to have the public in front of the FCC to tell them what it is. The doors to the FCC swung open and the preceding phase of corporatist politics was jettisoned in favour of public participation as a result.

The CRTC followed course a decade later, in 1976, but on its own accord after its remit was expanded to take over telecommunications from the Canada Transport Commission. Immediately upon taking over telecoms, the CRTC candidly announced the following:

… In a country where essential telecommunications services are provided largely by private enterprise with some degree of protection from competition, the public interest requires that those services should be responsive to public demand over as wide a range of possible, and equally responsive to social and technological change.

The principle of “just and reasonable” rates is neither narrow nor a static concept. As our society has evolved, the idea of what is just and reasonable has also changed . . . . Indeed, the Commission views this principle in the widest possible terms, and considers itself obliged to continually review the level and structure of carrier rates to ensure that telecommunications services are fully responsive to the public interest.[1]

Indeed, these ideas and values stand as a consistent thread between then and now: the Commission sets what constitutes basic service in light of constantly evolving technological, economic, social and political realities. That such ideas were in the air at the CRTC in the mid-1970s was also not anomalous but part and parcel of the times as well. Schultz offers a glimpse of this when he mentions the Department of Communication in passing (see para 46). However, the DOC is more important than he leads on. It articulated a broad vision of the “wired society” that it saw as being on the immediate horizon as broadband networks converged with computing and a cornucopia of information and media services to become the infrastructure of society in the near future. We’re here now, even if Telus hopes that the DOC’s broad vision is not.

Such ideas play little role in Schultz’s account and thus in helping us understand universal service and its evolution over time. They are part of what he thinks is a moment when the politics of universal service does emerge for the first time, but they are not given the gravitas that they probably deserve nor are they stitched into the flow of time – backwards or forwards – in ways that they need to be. As a result, the argument that was the closing decades of the 20th Century there were a watershed moment when the values, ideas and politics of universal telecoms services emerge for the first time is incorrect, for all of the reasons indicated above.

Look Where Things Are Not Where the Light Shines Brightest

Finally, and as I told the Commission last week and in my response to Telus’ questions to me earlier, most countries do not legislate specific affordable broadband service targets. Instead, the normal practice is to pursue broadband targets as a matter of public policy, developed and back-stopped by regulators and policy-makers that have the legal and political mandate to do what they need to do to achieve outcomes that are in the public interest. And this is as it is in Canada as well.

Ultimately, Schultz’s history is fundamentally flawed. Its main function appears to be to marshal scholarly credibility and legitimacy in the service of those who seek a specific, strategic outcome. It is a poor piece of research and hopefully will be given very little attention by the Commission, or anyone else for that matter.

Universal service for an all-IP world is something that we have to arrive at. It will not be easy. But an already difficult task won’t be made easier by those who use and abuse history for their own strategic ends.

[1] emphasis added, CRTC (1976). Telecommunications Regulation – Procedures and Practices (prepared statement). Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services.

Guilty Pleasures and Proper Needs: Who Gets What Kind of Internet, and Who Decides?

On Tuesday night I joined several other speakers at the Internet4All public forum held by ACORN, an advocacy organization that works on behalf of low- and moderate-income families in cities and neighbourhoods across Canada. The event was part of the run up to today when ACORN and its other partners in the Affordable Access Coalition[1] plan to tell the CRTC basic telecoms service review that broadband internet access is expensive and out-of-reach not just for people in rural and remote areas – the focus of many of the presenters in the first three days of the Commission’s review – but for people with low incomes in cities across the country as well.

ACORN’s Internet4All Public Forum

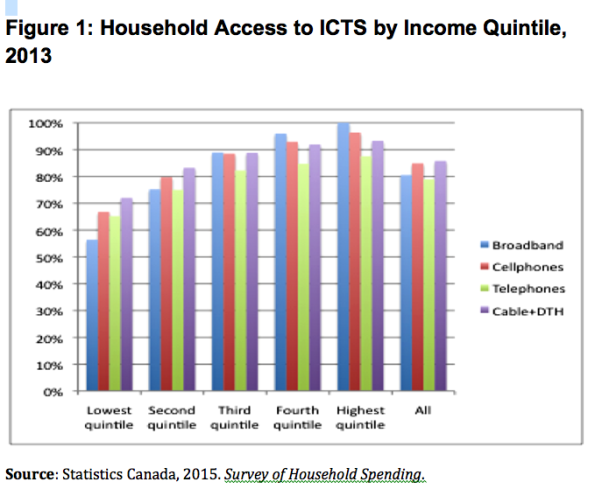

The link between income, affordability and internet adoption is clear, even if the exact causal links between them are not. Thus, while 80% of households in Canada subscribe to the internet from home, 2-out-of-5 of in the lowest income bracket do not, and one-out-of-every-three Canadians do not have a mobile phone. At the top of the income scale, in contrast, adoption levels are close to universal at over 95% for both. The figure below illustrates the points. While some wonder if this is because some people might not want to use the internet, the strong relationship between income and adoption suggests that this is not a choice but a function of affordability. Moreover, study after study tell us one thing: that the price of broadband internet and mobile phone services in Canada are high by the measure of all respectable studies of the issue (see, for example, the Wall, OECD and FCC reports). The high prices these studies document might account for a modest portion of the budget for the “average Canadian”, but for low- and modern-income families they compete with putting food on the table and a roof over their heads.[2]

While some wonder if this is because some people might not want to use the internet, the strong relationship between income and adoption suggests that this is not a choice but a function of affordability. Moreover, study after study tell us one thing: that the price of broadband internet and mobile phone services in Canada are high by the measure of all respectable studies of the issue (see, for example, the Wall, OECD and FCC reports). The high prices these studies document might account for a modest portion of the budget for the “average Canadian”, but for low- and modern-income families they compete with putting food on the table and a roof over their heads.[2]

Such realities also help to describe why, at best, ‘wired broadband internet’ adoption rates in Canada fare only reasonably well compared to other developed countries, but terribly for mobile wireless services. That affordability is clearly an issue is also illustrated by the fact that in Toronto, for example, just 20% of households in public housing communities have broadband internet service. These are the realities that are motivating ACORN members, and why the advocacy group is going to the CRTC today.

While the industry has done little to counter these realities, at least one has taken voluntary steps to help ameliorate the problem for some: Rogers. In 2013, it launched its ‘connected for success’ initiative with the aim of bringing affordable broadband internet access to 58,000 low income families in Toronto public community housing. Last week, Rogers came to the Centretown Citizens Ottawa Corporation to announce that the program is being extended to 150,000 families in 533 public housing communities in Ontario, New Brunswick and Newfoundland & Labrador for the next two years.

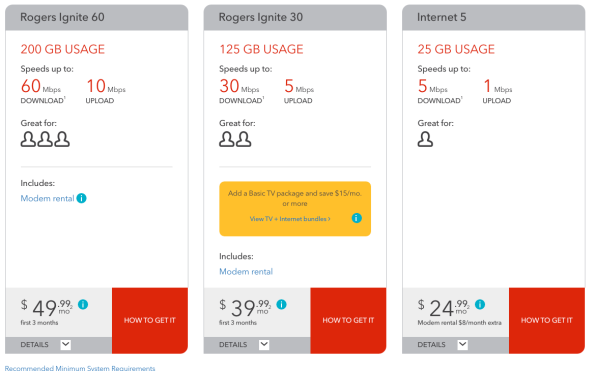

In its expanded “connected for success” initiative, Rogers offers broadband internet with speeds of up to 10 Mbps download and up to 1 Mbps upload, with data caps of 30 GB, for $9.99 per month. As a voluntary effort, this is certainly a step in the right direction.

At the same time, however, announced on the eve of the CRTC’s review of the basic telecoms service it is hard not to see the venture as a fine example of “regulation by raised eyebrow”, wherein just the threat of regulatory action brings about some gestures toward the desired results.

The people attending ACORN’s internet4all forum also suggested that while Rogers’ focus on non-profit community housing is good, the vast majority of low-income families do not live in social housing but market housing. Who will serve them?

In Ontario alone, 168,000 families were on the waiting list for community housing last year. This is more than Rogers is targeting across all of Central and Eastern Canada! For them, the cheapest option Rogers offers is its newly launched “Internet 5” service, but it offers only half the speed of the public housing option and is three times the price, once the cost of renting the modem is factored in.

Perhaps the biggest drawback is that these services are designed for individuals rather than households with several family members who might be running multiple devices at the same time, as Rogers’ own marketing materials on its website indicate. It is not just that the speeds are slow but that the data caps for both services — 30 GB for the public housing version, 25 for the latter – are exceedingly low. Cisco, in contrast, estimates the average Canadian household used 56 GB in 2014, and is expected to reach around 180 GB by 2019.

Figure 2: Rogers Internet Service Plans Compared

And what about the punishing overage charges that come along with those low data caps? On this, many of those attending the internet4all event the other night had a lot to say. Lastly, what happens to those who sign up for “connected for success” when the program meets its expiry date in two years?

Some argue that some access is better than none. More specifically, there are those who assert that when it comes to defining basic internet service, the aim is to give people basic broadband internet based on need rather than wants and desires.

We have certainly heard a lot of this kind of thinking already. Telus, in particular, argues that the only change the CRTC should consider is making the current “aspirational target” of 5 Mbps up and 1 Mbps down for all Canadians a formal obligation (see here, for example). In response to all those who claim that the standards of 25 and 30 Mbps up and 3 down adopted in the US and 28 EU countries, respectively, and that apply to all citizens and which must be met, as the FCC in the US puts it, a “reasonable and timely fashion”, Telus says humbug.

Over-and-against the view that anything less than these standards are not up to how individuals and families actually use the internet, especially in terms of viewing video and using multiple devices at the same time, Telus takes a flinty eyed view to argue that things like

. . . email access, web browsing and e-commerce . . . are the services that are necessary for meaningful participation in the digital economy. It is not reasonable to include over-the-top video and H-D two-way interactive gaming as essential applications that must be supported by Internet access faster than TELUS’ recommended 5/1 Mbps BTS (Telus, paras 90-91).

The Commission also appeared to strike a similar note when Chairman J. P. Blais kicked off proceeding Monday morning with the remark that the basic service objective must be firmly grounded in evidence, and that “it is crucial not to confuse ‘wants’ with ‘needs’”. Some chimed in immediately that Blais’ words reflected a “disciplined start”, while the CBC, in contrast, interpreted the remarks to imply that the Commission had already trimmed its sails and people ought not to expect much. Already by the end of first day, however, the Commission seemed to soften its tone.

Drawing the lines between basic needs and productive uses along such lines and whatever else people might do with their internet connections smacks of a long and hoary history where people have been told that what they use the media at their disposal for should take a backseat to more “important” uses, and consequently frowned upon and discouraged as a result. When I expanded on this idea at ACORN’s Internet4All forum, people got up one after another to give rhyme and verse on why such distinctions are not only wrong-headed but objectionable.

Why should people and families with low incomes — precisely the ones most likely to “cut the cable cord” to save money — be told that watching TV is beyond the pale. Isn’t it enough that they be able to do so without affordable basic internet access being hedged about by so many narrow and utilitarian values as to rule out such pleasures?

On this point, I heard much about Netflix and cartoons, and how telling stories, art and culture are essential to who we are as human beings, to our imaginations, and how we express ourselves. The gentlemen who relayed the bulk of this line of thinking will be there to tell the CRTC the same today.

And what about using the internet to get the news, a point that Chairman Blais also appears to fully grasp, given his remarks that with the French language newspaper LaPresse being available online only now, people have to have an internet connection to read it? This chimes with the results of a recent Statistics Canada study on how people “get the news”. As the video component of online news grows, it is going to become a lot harder to carve out this bandwidth intensive aspect of online news from the low capacity text based part.

Another person observed that as government departments put more information online they are also putting it online in video form. She pointed to Health Canada videos on palliative care and diabetes to illustrate the point, and to the essential role that these videos play in educating people and raising awareness about both conditions. How to distinguish between such “worthy” forms of high bandwidth intensity video and the frivolous kind we don’t hold aloft?

Another woman spoke about how her hearing impaired partner communicates regularly with her family back home in Australia by video and how doing so is not only crucial to their relationship but to her partner’s mental well-being more generally. Then there was another woman who spoke of coupon cutting online because, well, all the coupons are now online, and so too, by the way, are most of the rental housing advertisements.

A young man came up afterward and spoke to me about working a grueling 70+ hour work week throughout high school because both of his parents were on the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP), and the income they received was not enough to make ends meet. Despite being in the “gifted class” at Lisgar Collegiate here in Ottawa, with an average over 90%, his role of main family breadwinner meant that he had to drop out, unable to meet the competing demands of doing both. Yet, a few years later he completed an internet-based high school course, much of it based on instructional videos and video conferencing. He’s now at Algonquin College with hopes to complete his studies at Carleton when finances allow.

Another helped a friend faced with a $190 repair bill for a broken washing machine that she could ill afford. Instead of calling the Maytag repair guy, he turned to Youtube, found a $3 solution, and his friend kept her much needed money for other pressing uses. As a recent MTM study observes, nearly two-thirds of all Canadians used Youtube to learn how to fix or do something in the last year.

Of course we can pile up anecdotes like leaves in autumn but the point is, that even those of us who study these matters full-time don’t have a clue about many of the things that people do with the internet, for both pleasure and productive purposes. I see little way to effectively distinguish between the two and don’t think that much good will come from trying.

That we don’t know the half of what people do in their uses of media comes as no surprise to communication scholars because if the field teaches anything, it teaches that people use communication technologies in unintended ways and that this in turn pushes those technologies along unanticipated paths of development. Any effort to distinguish between “basic” uses that people should have access to as part of an affordable broadband internet obligation and those they shouldn’t risks running roughshod over these lessons. Worse, it risks substituting the regulator and carriers’ judgments for what people themselves are in the best position to decide.

As I pointed out in my testimony to the Commission the other day, providing people with affordable, universal broadband internet in the 21st century is a necessity, and it is in line with what we have done historically in Canada in relation to plain old telephone service. And it is in line with what other countries comparable to ours are doing around the world.

To be sure, this is going to cost money, and that means that somebody’s going to have to pay and who ultimately pays will be us — citizens and taxpayers. I do not see a problem with that.

Total federal subsidies for broadband internet development and affordable prices in Canada are at the very low end of the scale at around $2 per year. This is similar to what people in Bulgaria, Romania and Austria invest, whereas I think we could easily move into the middle of the pack to spend, say, $4.50 to $12 a person per year as they do — that is 40 cents to a buck a month extra on our internet bills — in Sweden, Estonia, the UK, Germany and Finland to subsidize internet development (compared to NZ and Australia at $25 and $163, per person, per year, respectively, for their own national broadband initiatives).

Consider this as well: In Canada, compare the $2 per person per year in total federal subsidies for broadband connectivity to the $33 given to the CBC, by contrast. The point is not to bring the latter down to the former by any stretch of the imagination, but rather to bring broadband subsidies closer to those that we give to the CBC (to say nothing of the myriad of other ‘content subsidies’). In the internet age, while content may be king, it is connectivity that is probably emperor. Our public funding arrangements should better reflect such priorities.

Ultimately, any steps to draw lines between frivolous wants that we can cast aside and productive uses that can be folded into basic internet service will likely look, at least in hindsight, like so many similar such efforts in the past: as paternalistic and elitist efforts, and foolish ones at that. The Commission should give little credence to such ideas, and indeed should reject them out of hand. Get the structure of the internet policy framework right, and the rest will likely fall into place as it should.

For these reasons, we need less flinty-eyed, utilitarian outlooks drawn from Victorian England and a more imaginative view of the future, albeit one that is still grounded in what people are already doing with the internet and plenty of room to grow so that all Canadian citizens can use the internet as they see fit, both today and tomorrow.

[1] Which also includes the Public Interest Advocacy Centre, Consumers Association of Canada, Council of Senior Citizens Organization of BC and the National Pensioners Federation.

[2] On this measure, Canada ranks in the middle of comparable EU and OECD countries according to the ITU, see pp. 102 and 109, for example.

Carleton Study Challenges Claims of Big Wireless Players and Promotes Need for Maverick Brands

Cross posted from Carleton University homepage.

Well, this is a bit of a cheat, but Steven Reid at Carleton University did such a great job conveying the central message of a new report that we put out at the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project that I thought I’d just crib the whole thing and re-post it here. Thanks Steve.

Steven’s wordsmithing follows:

Carleton University’s Canadian Media Concentration Research project, directed by Dwayne Winseck of the School of Journalism and Communication, has released a report entitled Mobile Wireless in Canada: Recognizing the Problems and Approaching Solutions. The study outlines the state of wireless competition and concentration in Canada in relation to 57 countries worldwide, covering a period of three decades.

“The deep divide between the wireless industry and the government that has erupted over the latter’s attempt to reduce domestic and international roaming charges and foster more competition is the focus of the study,” said Winseck. “The study challenges the industry’s claim that there is no competition problem in Canada and emphasizes the importance of maverick brands that extend the market to those at the lower end of the income scale – women and others who are otherwise neglected by the well-established wireless players.”

The report supports the assertion that mobile wireless markets in Canada are not competitive. It offers a comprehensive, long-term body of evidence that places trends in Canada in an international context. The study shows that Canada shares a similar condition with almost all countries that were studied: high levels of concentration in mobile wireless markets.

The difference between the wireless situation in Canada and elsewhere is the lack of resolve to do anything about this state of affairs said Winseck. The study concludes that Canada’s situation is not promising, although there are some bright spots on the horizon.

“For the time being, the tendency is to deny reality, even when incontrovertible evidence stares observers in the face,” said Winseck. “This, however, is symptomatic of a bigger problem, namely that in Canada the circles involved in discussing wireless issues are exceedingly small and they like to hear the sound of one another’s voices. Their members do not look kindly on those who might rock the tight oligopoly that has ruled the industry from the get-go.”

The study highlights the importance of emerging maverick brands like T-Mobile in the U.S., Hutchison 3G in the U.K., Hot Mobile and Golan Telecom in Isreal, and Iliad and Free in France.

Maverick brands have many things in common:

- All have faced aggressive incumbents and they tend to disrupt the status quo, pushing down prices, driving massive growth in contract-free wireless plans and unlocking phones.

- They have relied on the state for a fundamental public resource that underpins the entire mobile wireless setup: spectrum.

Incumbents have fought against new wireless companies, challenging governments in an attempt to preserve their domination of the spectrum. In Canada, three companies currently hold 90 per cent of the spectrum: Rogers (41 per cent), Telus (25 per cent) and Bell (24 per cent).

The study shows that compared to the countries included in the study:

- Wireless markets in Canada, regardless of how they are measured, are remarkably concentrated;

- Canadians are first in terms of time the spent on the Internet, GBs of data uploaded and downloaded, smartphone data sent and received etc.;

- Canada is highly ranked when it comes to capital investment in its wireline infrastructure, but lags in wireless investment.

“Whether or not people get the media, wireless and Internet capabilities they need to live, love and thrive in the 21st century depends on making the right choices now,” said Winseck. “Those choices are staring Canadians in the face. How we act, and how our government moves ahead, will set the baseline for how mobile wireless media in this country will evolve for the next two decades – the length of the licences being awarded in the upcoming 700 MHz spectrum auction – and probably for a lot longer than that.”

An executive summary of this study can be found at: http://www.cmcrp.org/2013/11/18/executive-summary-the-cmcr-projects-wireless-report-mobile-wireless-in-canada-recognizing-the-problems-and-approaching-solutions/

The full report can be viewed at: http://www.cmcrp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Mobile-Wireless-in-Canada2.pdf

Ask the Wrong Questions and . . . : the CRTC’s Review of Wireless Competition

In the middle of last week the CRTC began to solicit views on whether or not a national code for wireless services is necessary. The CRTC had received several applications, it said, suggesting that such a code might be needed.

Who might want such a code? The big wireless providers, Rogers, Bell and Telus, that’s who, and their lobby group, the Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association.

Why? Because they’ve been facing mounting efforts at the provincial level to more strictly regulate their pricing and service packaging. Ontario, Manitoba and Quebec have been leading the way (see here). Rabble rousing Openmedia also has the wireless industry in its sights with its “stop the squeeze” campaign (also see the Open Media/CIPPIC study here). A standard code generated by the industry could help dampen the clamour.

In its notice, the CRTC wondered aloud about whether its reliance on competition to the maximum extent possible in wireless, and its decision way back in 1994 to not regulate the sector, might be misguided in light of stubbornly low levels of competition. Anybody who thinks the regulator should actually do something has to (a) show the circumstances have in fact changed and (b) that this change represents a turn for the worse. Only then will the CRTC intervene.

And if does intervene, what can we expect? Not real regulation, but rather a “national code for wireless services” designed by and mostly for the industry.

So, have things changed? Well, yes, of course: 2G, 3G, now 4G and LTE. Smart phones are increasingly making their ways into the palms of Canadians across the land. The internet of devices is highly wifi dependent, and mobile data and video use is growing fast. The industry has also grown from a $3.7 billion industry in 1996 to $18 billion in 2010.

However, one thing that has stayed constant is the fact that the wireless services have never been truly competitive and likely never will be. Nor, however, is it necessary that we expect them to be. But the CRTC said that it would need evidence to indicate that market forces are not working before it would act.

Let me introduce two such indicators: one, the empirical evidence on the state of competition and concentration in the wireless sector between 2000 and 2011 and, two, some indicators of price and quality drawn from relevant global standards.

1. Competition and Concentration: In 2000, the big three wireless providers — Bell, Rogers and Telus — accounted for just over 87% of the industry. Today, they account for just over 93%. The “big three” control more of the sector than ever, and besides that Rogers and Bell now straddle every other significant segment of the telecom-media-internet industries. What they do in any one of these areas affects the developments elsewhere, and broadband wireless services in particular.

The wireless industry was already highly concentrated in 1994 when the CRTC decided that the market was competitive enough to stop doing what it’s suppose to do: regulate. Competition did increase modestly during those early years, with two new rivals – Clearnet and Microcell — snatching away 12 percent of the market away from the incumbent telcos and Rogers by 2000. The two rivals were short-lived, taken over by Telus and Rogers in 2000 and 2004, respectively.

Competition peaked in 2000, then the sector became sharply more concentrated by 2004, before falling slightly and staying relatively flat ever since. Whether recent newcomers — Mobilicity, Wind Mobile, Public and Quebecor — will fare any better, it is still too early to tell. With only 2.7% of the market as of 2011, they are far off the mark set at the high-point of competition in 2000.

The graph below charts the trend between 2000 and 2010 using the Herfindhahl – Hirschman Index (HHI). Remember, the basic rule with the HHI is that scores under 1000 indicate reasonable competition, 1000-1,800 moderate levels of concentration and anything over that, high levels of concentration. They’ve been over 3000 for most of the decade.

HHI scores for the Wireless Sector, 2000 – 2010

Sources: CRTC’s Communications Monitoring Report for 2008 and 2010, and the Telecommunications Monitoring Report from from 2000 to 2007, Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association’s Wireless Phone Subscribers in Canada.

While there’s room for interpretation, the bottom line is that the wireless sector is and always has been highly concentrated. It is less competitive now than it was in 2000, when ‘market forces’ peaked. The CRTC is right that after this length of time, and in the face of the immovable reality of high levels of concentration, yes, maybe it is time to temper the ‘maximum reliance on market forces’ mantra. A code may just be in order, although one might go even stronger and ask for proper regulation, i.e. for the CRTC to do its job versus playing overseer to an industry-developed code.

2. What about Prices and Quality?

In terms of prices, we can look at things charitably and not so charitably. First, we can look at the CRTC’s data for information on pricing for wireless services, but we’d look in vain. The best I can see is a combined price index for wired and wireless telephone service in comparison to the cost of cable and satellite services as well as Internet access services. The figure shows the trend below.

Source: CRTC (2011). Navigating Convergence, p. 65.

Seen from this angle, things look not too bad, at least between 2002 and 2007, when prices were falling below the level of the general consumer price index. The situation reversed after that, however, with the price of wireless services rising relative to the cpi since 2007. Prices have not risen as fast as in cable and satellite subscriptions, but they have not fallen to nearly the extent as they have for Internet access.

We can also look at this relative to seven other countries that can be meaningfully compared with Canada. As the following figure drawn from the UK regulator, Ofcom, shows, the amount that Canadians pay to their wireless provider each month is at the high end of the scale and always has been throughout the period covered. Also note that prices in every other country surveyed, except Australia, have been falling, while in Canada they’ve been on the rise.

Source: Ofcom (2011). International Communication Monitoring Report, p. 256.

We can also look to the OECD for some guidance. In terms of wireless broadband access per 100 people, Canada ranks 26th out of 34 countries. The following chart shows the comparison.

Source: OECD (2011). Broadband Portal.

Of course, there’s much more that could be said, but just from a cursory glance, all is not right in the wireless kingdom. Of course, many seem to think that opening up foreign investment is the way to go. As I’ve said before, I’m not so sure. Now is not exactly the high-tide of foreign investment in mobile services, at least in the Euro-American economies. And many of those same sources seem to have the US in mind when they hope that big foreign investors will come in to save us from the rapacious grip of Rogers, Bell and Telus. I’m afraid, however, as Susan Crawford, amongst others observe, the US is no better than here, and even more of a basket case on some measures.

The upshot of all this: wireless will likely never be competitive. The CRTC needs to regulate versus oversee an industry-developed code. Lastly, instead of auctioning off all the spectrum, Industry Canada should look to develop an open wireless model.

Crony Capitalism?: Revolving Door between Telecom-Media-Internet Industries in Canada and Ex-Politicos

Where do ex-politicians go when they retire? It would appear that they take up sinecure amongst the boards of directors at Canada’s leading telecom-media-Internet (TMI) companies.

The appointment of recently retired Industry Minister Jim Prentice to Bell Canada’s board of directors and Stockwell Day’s appointment to Telus, respectively, in the last two weeks has tongues wagging. Many think it ain’t right, others see no problems; I see it as business as usual, systemic and a big problem that contradicts the ideals of a free press and any notion that TMI policy in this country is anything more than industrial policy and a major industry player protection racket.

Of course, not everyone sees things this way. As one lobbyist from the software industries in Canada badgered me over the weekend on Twitter, what’s an old political hack suppose to do when they leave office? What’s wrong with Prentice and Day taking up shop at Bell and Telus?

Well, lots. If it was just Prentice and Day stepping from the halls of Parliament to paneled boardrooms of Corporate Canada, perhaps it would be exceptional and not much to be worried about. However, if we look at the boards of directors at the top ten TMI players in Canada, we see that they are not the exception but the rule. The boardrooms are brimming with their type, with a total of fourteen directors – an ex Prime Minister (Brian Mulroney at QMI), an ex-first lady (Mila Mulroney at Astral), two former Chairpersons of the CRTC (Francois Bertrand at QMI and Andre Bureau at Astral, and more, as the chart below shows – occupying these coveted spots.

Top 10 Telecom-Media-Internet Companies and the Ties that Bind

| Ownership | Politicos as Directors | Family Members as Directors | Links With Other MediaCos | |

| Astral | Greenberg | Andre Bureau (CRTC chair) |

3 |

Paul Godfrey (PostMedia) |

| Mila Mulroney | Phyllis Yaffee (Dir. Torstar) | |||

| Bell | Publicly Trade (Diversified) | Jim Prentice (Cons. Ind. Minister) | Not Relevant | |

| E. C. Lumley (Lib. Cab. Min) | ||||

| Carole Taylor (BC Fin Min) | ||||

| Cogeco | Audet (64%) |

1 |

||

| Rogers (36%) | ||||

| PostMedia | Godfrey (6.5%) | David Emerson (Lib. Cab. Min) |

1 |

|

| Quebecor | Péladeau | Brian Mulroney (Cons. PM)Francoise Bertrand (Chair CRTC)Kory Tenycke (VP Sun News, ex Harper Dir. of Communication) |

1 |

|

| Rogers | Rogers | John H. Tory (ex. Ont. PC leader)David Peterson (ex Lib Premier Ont.) |

4 |

Issabelle Marcoux (Transcontinental |

| Shaw | Shaw | Sheila Weatherhill (PM Advisory Cmmt on Public Service) |

3 |

|

| Torstar | Atkinson, Thall Hindmarsh, Campbell, Honderich | Roy Romanow (ex Premier of Saskatchewan) |

2 |

Phyllis Yaffee (Dir. Astral) |

| Globe & Mail | Thomson (65%) |

2 |

||

| OTPF (25%) | ||||

| Bell (15%) | ||||

| Telus | Publicly Traded Diversified | Stockwell Day (ex CPC Cab. Minister) | Not Relevant | |

|

14 |

16 |

Sources: Corporate Annual Reports and Forbes Corporate Executives & Directors Search Directory <http://people.forbes.com/search>

Things are particularly strange in Canada by the added fact that eight of the top ten TMI companies in this country are family-controlled. This degree of media mogul control and political ties to the inner sanctums of top media companies is reminiscent of an ‘ancien capitalism’, where families and the ‘political class’ are in charge rather than citizens and ‘expert’ managers at the helm of publicly-traded firms where ownership is dispersed and corporate operations transparent.

Things are different in the US, where Eli Noam points out in his authoritative Media Ownership and Concentration in America that the number of owner-controlled media firms fell from 35 percent to just 20 percent between 1984 and 2005 (p. 6). I think that Noam slightly exaggerates the decline given that five of the top global media conglomerates — Comcast (the Roberts family), News Corp (Murdoch family), Viacom-CBC (Redstone family), Bertlesmann (remnants of Bertlesmann and Mohn families) and Thomson Reuters (Thompson family) – are of this type. Moreover, the media baron still cuts a large figure at the top ICT and Internet companies to, think: Apple (Jobs), Facebook (Zuckerberg), Google (Page, Brin and Schmitt), Microsoft (Gates and Ballmer), Yahoo! (Yang), IAC (Diller and Malone) and CBS (Redstone).

The ongoing case of the telephone hacker scandal in the UK reminds us that with the Murdock family – Rupert and his son James – at the helm, we are far from the end of the era when media moguls ran supreme. Thus, while not totally unusual, the degree of ties between moguls and political appointments at Canada is of a different kind and more extensive. Such arrangements are backwards, if you will, and more like nations with a tradition of oligarchic capitalism, as in Russia and Latin America, then in the liberal capitalist democracies of the US and Europe.

It is not that we just have an outmoded system of family control with ex-politicos having positions of influence right across the ranks of TMI sectors, but also that the main players have ownership stakes in one another’s companies, as is the case with Rogers owning about a third of the equity in Cogeco and Bell a residual 15 percent stake in the Globe and Mail.

Also blunting the sharp edge of competition and independence between different players in the market is the fact that directors on the board of one company sit on the boards of supposed rivals. Phyllis Yaffee, an industrial stalwart with oodles of experience and one who actually does have the expertise and savvy to fill a directors’ shoes is on boards at Astral and Torstar. Paul Godfrey, also an old hand and savvy operator in the business, sits on the boards at Astral and PostMedia Co. — the company a company that he has spearheaded the development of to assume ownership of the twenty odd newspapers (Ottawa Citizen, Windsor Star, National Post, Calgary Herald, Montreal Gazette, etc.) left behind by the wreckage of Canwest. That wrecked vassal is yet another company that was family controlled (the Aspers) and not shy about stacking its board with ex politicos (e.g. Derek Burney, ex. Chief of Staff for Harper).

We also, as I have said repeatedly in this blog and elsewhere, a very highly concentrated set of industries. Altogether, the big 10 firms listed in the table above account for just under three quarters of all revenues in the TMI industries (excluding wired and wireless telephone services). I think the two are related.

It is not just that all our TMI industries, individually and as a whole, are very highly concentrated, but that policy and regulation in this country does not deal with this fact. Instead, policy-makers and regulators, to a large degree, cultivate concentration on the grounds that whatever problems this raises will be offset by industrial gains.

As David Ellis pointed out the other day, the CRTC does not regulate the TMI industries on the basis of any known standards of market concentration, but functions primarily to grease the supply-side of the industrial machinery that make up the TMI sectors.

The problem is not just that this leaves consumers and citizens on the sidelines while industry calls the shots. The problem is that the phenomenon of politicos on the boards of directors at the major TMI companies, and the revolving door between the regulator and government policy-shops on one side and industry on the other are pervasive, enduring and systemic.

What this means is that we cannot just look for one-off instances of influence peddling, as in, say, the allocation of spectrum in past and forthcoming wireless auctions, as Peter Nowak points out. Nor is that putting Harper’s former Director of Communication, Kory Tenyecke in the position of VP at QMI’s Sun News will leave a dirty trail of finger prints on every story covered, with lurid tales of stories spiked and stories spun to favour Harper and the Conservatives.

To be sure, a few cases of such things will happen, with one or two leaking out to become grist for the mill and confirming some people’s worst fears. The problem is deeper than that, however, and less easy to suss out in terms of what it all means. However, as I showed during the election this year, it is true that of the twenty-two papers that issued endorsements for Prime Minister in the last election, all but one stood foursquare behind Harper — a wall of Conservative editorial opinion behind the Conservative candidate for PM.

Yet, the meddling hand of direct owner or political influence is much more subtle, and rarer than this. Instead it takes place at two more general levels: corporate policy making and the allocation of resources, say, resources for faster Internet connections, more journalists and coverage of world affairs and the environment versus cut-backs, low levels of investment and fluffy content to titillate and instigate bickering rather than understanding and civil discourse. It is at this general level that directors hold sway. Indeed, that’s what they’re hired for, to set long term policy and make sure that those directly controlling the purse-strings do so wisely.

Beyond this, the real problems are three-fold: First, the revolving door between regulator (CRTC) and those who make the rules while in government, on the one hand, and the TMI companies, on the other, institutionalizes an approach to media policy as industrial policy and a strategic game. The extent of this also means that everybody in the game must adopt a similar strategy, which only aggravates the problem and makes things all the less apparent in terms of who and what is really calling the shots.

Consequently, regulation and policy-making is not so much about guiding the development of telecom, media and Internet in relation to democratic and free press values but industrial policy concerns. As I stated earlier, the CRTC serves principally to grease the supply-side machinery of these industries, rather than regulating in the public interest or in relation to a broad understanding of how people actually use media facilities and what we want. Perhaps this is not surprising, given that the last known sighting of the CRTC’s old motto, “communication in the public interest”, was in December 2008 (see here). It has disappeared from the top of its webpage and prominent place on the front of publications ever since. No wonder some commissioners and the vice-chair have a hard time understanding the link between media and democracy.

Such arrangements are an affront to common sense and to principles of a free press in liberal capitalist democracies. They smell bad and smack of crony capitalism unfit by even the standards of liberal capitalist democracies.

Finally, they fly in the face of liberal theories of a free press. According to classical theories of the free press, and especially Whig tales of press history from the rise of advertising-funded mass media in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, the media are suppose to be independent of government. They are also to serve as a watchdog nurturing the public sphere rather than as waiting lapdogs for retired politicos in the hope that they can tilt the industrial policy-making game in their new masters’ favour.

Angels to Telus: Don’t be Evil

A reader, Sean, sent me an email yesterday, two actually and a couple of questions. They reminded me of something, and then inspired me to read and write. Thanks Sean.

The immediate point was that Shaw Media and Telus are about to ramp up bandwidth caps and UBB — the cornerstones of the the pay-per Internet model — in western Canada. To be sure, people in Alberta and BC have already had lots of this model already.

However, while both Shaw and Telus have had ‘bandwidth caps’ and UBB on the books, they have not used them. That looks set to change.

Shaw appears to be first off the mark in wanting to kick these into action, as it told, again, those pesky investment bankers who are now hovering around companies because it is the ‘end of quarter’ reporting season of its plans. As Shaw stated, it has the market power to impose the pay-per pricing model and supposedly the consent of its users. I don’t doubt the former, but the latter claim is circumspect.

Shaw has come full circle in the past sixth months after acquiring Global TV and has begun to sing a new gospel from the top of its lungs in favour of regulating OVP (online video providers) such as Apple TV, Google, Netflix, etc..

Telus, too, has had pretty tough bandwidth caps and UBB on its books. It’s cost per ‘extra’ GB when going over the cap is a punitive $2-5. Telus infamously shut down access over its ISP to the website “Voices of Change”, a site run by the Telecommunication Workers Union, during a strike in 2005.

It has been no angel. However, I am also reminded that amongst the ‘big six’ — Bell, Shaw, Rogers, Quebecor, Telus and Cogeco — Telus is something of an exception, or at least has a few characteristics that distinguish it from the others and put it on, as my friend Marc-Andre put it, “the side of the angels”. We should probably give credit where credit is due.

First, we must remember that in a situation where Canada stands unique, if not completely alone, in the universal coverage of ‘bandwidth caps’ and pay-per GB ‘excess usage charges’, Telus has not yet made the move to implement these measures and might yet be dissuaded. So, for what that’s worth: Telus, please don’t be evil.

Second, on some key ‘structural issues’ that go to the heart of the organization of the network media in Canada, Telus stands alone amongst the ‘big six’ for not following the path of ’empire’ by becoming vertically-integrated with a dominant broadcaster. This means that its voice has been absent among all of the others who have called in unison for the CRTC to regulate online video providers.

Third, Telus recently told the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage in no uncertain terms that it opposed the Shaw-Global TV and Bell-CTV amalgmations, respectively. In sum, Telus has not embraced the shangri-la of ‘media convergence’.

That, however, does not mean that it is not in the TV business. It serves as distributor of Bell satellite TV in the west. It has its own IPTV service, mobile tv channels, and so forth. It needs programs and ‘content’ for its IPTV service, mobile tv channels, and so forth as well, and therein lies a problem.

Telus already claims to be having a lot of difficulty getting the programming that it wants on reasonable terms. This is more grounds for its opposition to vertical integration still. For that reason, Telus will stake out a unique stance at the upcoming CRTC hearings on vertical integration in being the only major incumbent likely to argue on behalf of some form of structural separation. This is a good thing and, again, Telus is on the side of the angel

Having just been blessed by the CRTC (and Competition Bureau) over the past six months, it is hardly likely that the CRTC will do much more than tinker around the edges with vertical integration. The fact that Industry Minister Tony Clement has already voiced his view that vertical integration is the way of the future and structural separation irresponsible only reinforces the impression.

All of this reminds me that the commitments to open networks is not about paying homage to abstract principles but to a concrete trilogy of real considerations: open networks, open sources and open societies. At the present conjuncture, each is under severe pressure, but yet to be bowed.

While no angel, Telus is on the side of the good with respect to open networks and should be applauded to the extent that it is. In terms of open source, the approach helps generate ideas, examination and conversation like Sean’s email did yesterday. Several others have written lately too, so thanks, but I would also like to suggest that it is best to raise issues here. That way others can weigh in, and go off on their own, too.

These are also the things upon which an open society — the ultimate endpoint of the trilogy to begin with — depends. There are important questions about just how far Canada has fallen from that standard.

We have corporate disclosure rules that pale alongside those in the United States. Not just the major network media conglomerates, but publicly-traded corporations in Canada generally disgorge far less information to the CRTC and Competition Bureau than their counterparts in the US are required to do by the FCC and Department of Justice.

The Harper Government has clamped down on information flows and the general tenor it has set has simultaneously fortified and calcified the historical proclivity towards information secrecy in Canada relative to other capitalist democracies. Without a full-commitment to open societies and open sources and open networks, none of these elements can flourish on their own. It is a thought worth bearing in mind, I think.