Archive

The CRTC’s Latest Talk TV Decisions: Sweeping Change or Plus Ça Change?

Yesterday the CRTC announced the second phase of its Talk TV decisions (Blais Speech; Decision). The Commission’s efforts are being cast as a significant overhaul of the regulatory framework for TV in Canada, but are they?

Out with the Old (Maybe)

Cast against the anachronism of film and TV quotas forged in the 1920s when Canada was still a member of the British Empire and the CBC just coming into being a decade after that, followed by the Broadcasting Act of 1968, and a long chain of events ever since, Blais’ message was clear: the regulatory edifice built up over the past century must be cleared away. The 21st century is the “Age of Abundance”, and with people increasingly using broadband internet and mobile devices to access content from around the world, the time for change is now.

Some Significant Steps Forward

At the top of the list of things to be discarded are Canadian content quotas during daytime hours. In prime-time, half the hours must still be filled with Cancon while quotas for pay and specialty cable channels have been harmonized downwards to 35% versus their current range from 15-85%. Genre protection for specialty TV channels will be eliminated and licensing requirements for discretionary channels with less than 200,000 subscribers have been dropped.

These moves open room for new services to emerge and could make it easier for people to pick and pay for TV channels they want — depending on the next instalment of the CRTC’s “Talk TV” decision next week.

Another cornerstone of the CRTC’s new approach to TV is to go from protection to promotion, and from a focus on quantity to quality, it says. The CRTC wants to encourage the production of fewer but bigger budget, higher quality TV programs that it hopes can attract Canadian and global audiences. While such efforts have been in the works since the late 1990s, the greater sense of urgency attached to this goal and changes in the means to get there are new.

To such ends, two new pilot projects were announced to fund big budget productions. The Commission also encouraged the government to change the Canadian Media Fund so that financial support can be funnelled to fewer but larger production companies and without the requirement for them to have a licensing agreement in place with a broadcaster (read: Bell, Shaw, Rogers, Quebecor, or the CBC) — in essence cutting out the middleman and giving independent producers direct access to CMF financial support. There is also a push for more international co-productions, and to get the fruits of such efforts into as many foreign markets and as many distribution platforms as possible, from Netflix, to Apple, Amazon, and so on.

The CRTC also adopted measures that aim to help staunch the problems that have beset journalism in the past several years. To this end, TV news services will be required to dedicate at least 16 hours a day to original programming, maintain news bureaus in a least three regions outside their main live broadcast studio and to have the “ability to report on international events”. Given the fact that news budgets have been slashed across the country for years, one can hope that such measures may help to stem the tide.

Beware of Vested Interests Wrapping Themselves in the Flag and the Public Interest

In a world in which the forces of the status quo loom large, these changes will rattle some. Anticipating resistance from some well-established quarters, Blais took aim at those who would fight to turn-back the clock:

If you hear criticisms of our decisions ask yourself this question: Are the arguments advanced by these critics those of the public interest or are they rather those that find their true roots in private entitlement, dressed up to look like they are founded on the broader public interest? This town is full of lobbyists whose job it is to spin their client’s private interests into something else, to wrap themselves up, as it were, in the flag, and to puff about Parliament Hill with an air of shock and dismay.

Three Steps Backwards

If we stop the discussion here, then yesterday’s ruling appears to take on the industry and its’ phalanx of lobbyists in order to yank Canadian TV into the 21st century. However, other measures give cause pause for concern.

A Cull of Independent TV Production Companies is Needed

First among these is the CRTC’s view that too many independent television production companies exist, many of which are set up for one-off projects and then wound down. Pointing to an estimate that there are 900 such companies, the CRTC argues that

. . . This project-by-project system hinders growth and does not support the long-term health of the industry . . . . The current situation is no longer tenable. The production industry must move towards building sustainable, better capitalized production companies capable of monetizing the exploitation of their content over a longer period, in partnership with broadcasting services that have incentives to invest in content promotion.

Yet, stand back and questions immediately emerge. The idea that there are 900 firms appears inflated alongside the Canadian Media Production Association’s estimate that 350-400 such companies exist and that a quarter of them have been created for specific projects and wound down immediately afterwards. Moreover, about 20% of those firms account for 80% of the industry’s revenue.

The existence of a vast pool of precarious, short-term production outfits is the norm in the film and TV business, not just in Canada but LA, New York, Wellington, London, Mumbai, almost everywhere (see Tinic and Gasher). This has long been the case, not just in film and TV, but the publishing industry since the 16th century and across the cultural industries from the last half of the 20th century (see Miege and Thompson).

Finally, the CRTC’s notion that too many creators exist stands at odds with the idea that it is supposed to be fostering more diversity, not less. Moreover, it also sounds a lot like the tired old ‘national champion’ strategy which has created the highly concentrated telecoms and media industry and high levels of vertical integration that currently exist and which are the source of so many of the problems being faced today to begin with.

Tearing up the “Terms of Trade Agreements”

Yesterday’s decision discards the ‘terms of trade agreements’ between producers and the large vertically-integrated media companies – Bell, Shaw, Rogers, Quebecor – that were put in place in 2011 and 2012 after years of protracted negotiations. Consolidation has reduced the number of sources that producers can go to for financing, rights deals and distribution – the real levers of power in the ‘cultural industries’. The terms of trade agreements tried to offset this reality by creating standard terms of trade and a ‘use-it-or-lose-it” clause that required broadcasters to use the rights they acquired within a year or turn them back to the producer; international and merchandising rights were reserved for producers.

Disputes over such issues, especially for mobile and internet rights, continue. They were a cornerstone of license renewals in 2011 and 2012 and a key reason why many of the producer interests reluctantly signed off on Shaw’s acquisition of Global in 2010 and Bell’s take-over of CTV and Astral Media in 2011 and 2013, respectively. Discarding the ‘terms of trade’ deal is another victory for the vertically-integrated giants and a big loss for independent producers, as head of the CMPA, Michael Hennessy, intimated earlier today on Twitter.

Vertical Integration and “Tied TV”

The CRTC also treads lightly when it comes to TV services delivered over the internet and mobile, such as Bell’s CraveTV and Shomi, a joint venture by Rogers and Shaw. Unlike Netflix, or HBO, CBS’s “all access”, and other services in the US, these services are not available to everyone in Canada over the internet but tied to a subscription to one of Bell or its partners’ (i.e. Telus and Eastlink) TV services in the case of Crave TV or to Rogers and Shaw’s internet or TV subscribers in the case of Shomi. They are defensive measures designed to protect Bell, Rogers and Shaw’s existing business models and the established TV “system” generally.

If the CRTC really wanted to disrupt the status quo then these attempts to leverage old ways of doing things into the emerging areas of distributing TV over the internet and mobile services would have been a primary target for action.

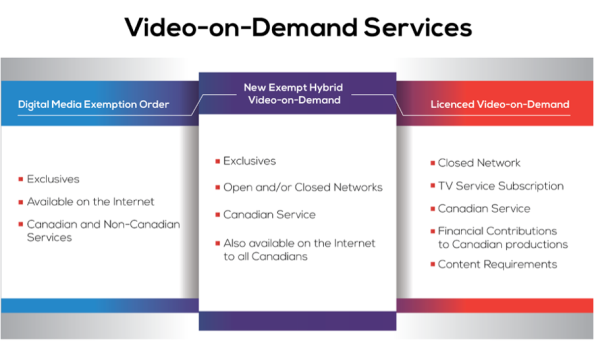

Instead of tackling the issue head-on, however, the ruling seems to skirt the issues by creating a new category — “exempt hybrid video-on-demand” model – intended to encourage companies to offer TV services to everyone over the internet without being required to subscribe to any of the companies’ other TV or internet services. In return, they could offer exclusive content and be relieved of obligations to fund and showcase Canadian content, as Figure 1 below shows. This is the same treatment that all stand-alone OTT services get under the Digital Media Exemption Order, but with the idea that such services could be distributed across the companies’ closed cable networks and the ‘open internet’ as well.

Source: CRTC (2015), The Way Forward, para 106.

Source: CRTC (2015), The Way Forward, para 106.

A Bell statement concluded that the decision will not change the way it offers CraveTV; Rogers has remained mum.

The ruling, however, puts the Public Interest Advocacy Centre and Consumers Association of Canada’s recent challenge against Crave TV and Shomi on the grounds that the services play fast and loose with the broadcasting and telecoms acts, as well as the CRTC’s Digital Media Exemption Order, on hold (see here). PIAC-CAC responded to the decision by saying that they

are skeptical today’s decision will have the effect of motivating Bell, and Rogers and Shaw, to make their content available online to every Canadian as a true ‘over-the-top’ service. . . . What today’s decision does not do is declare that Bell, Rogers and Shaw are such ‘hybrids,’ and therefore it appears that the commission will allow the closed, tied model to continue.

Plus Ça Change?

Reducing content quotas and eliminating genre protection are important departures from the past, while taking steps to foster better quality program production may produce fruit. The push to rationalize the TV production sector around fewer and more highly capitalized companies, tearing up the terms of trade agreement, and letting Bell, Rogers and Shaw’s ‘tied TV’ offerings off the hook, however, all appear to reinforce the power of well-established players who have pushed so hard to hold back the tides of change that the CRTC claims to be promoting.

No Regulatory Cherry-Picking Allowed: the CRTC vs. Netflix Clash @ the TalkTV Hearing

The final day of the CRTC’s hearing into the future of television saw a heated clash between CRTC chair Jean-Pierre Blais and online video distributor Netflix. It was a moment with few precedents, and one ripe with a myriad of fascinating questions (Netflix presentation here; CPAC coverage here).

The clash ignited when Blais’s request to Netflix’s Director of Global Public Policy, Corie Wright, to file information with the commission about the number of subscribers it has in Canada, its revenues in Canada and other information the company does not routinely disclose was met by much hesitance on Netflix’s part. As Wright repeatedly returned to concerns about confidentiality, Blais testily questioned whether Netflix did not trust the CRTC’s ability to deal fairly with companies’ request for confidentiality.

The problem, however, is that while Netflix demanded guarantees of confidentiality, it is the CRTC’s prerogative to determine whether such requests outweigh the public interest in disclosure. And in this regard, Blais refused to concede that prerogative while Netflix was equally intent on assuring confidentiality for information that it never gives out to anyone, no matter who asks.

While that may cut it when it comes to researchers and journalists, it won’t do in the context of a CRTC hearing that is, after all, a quasi-judicial proceeding with stringent legal standards about evidence. The point was made on the opening day of the “Talk TV” hearing as well when a similarly frustrated Blais encountered PR puffery from Google that hardly constituted robust evidence that could be used to shed light on anything other the company’s own interests and story that it’d like to tell the world.

This is not novel and is, indeed, well-established practice. Indeed, for all those who play in the regulatory arena, there is little more frustrating than the extensive use of the infamous hashtag (#) in instances that the CRTC has granted companies confidentiality over those who have sought disclosure. Indeed, for many, the problem is that the CRTC has been too generous in granting confidentiality over disclosure. So, to have Netflix say that it was seeking to pre-empt the question by having guarantees of confidentiality from the get go was beyond the pale, and Blais treated it as such.

So, where do these trade-offs between confidentiality and disclosure come from? Three places.

First, from the general tradition of regulated industries where the interest of the public in the matters at hand are always weighed against business demands – typically expansive – to keep their affairs private.

Second, the CRTC took up the issue in 2007 in a proceeding about just this issue where the Commission observes the following:

. . . [The CRTC] conducts its public processes in an open and transparent manner. In some instances, parties submit information in the course of proceedings for which they request confidentiality. . . . [O]ther parties to the proceeding may request public disclosure of the information. If such a request is granted, the information is put on the public record. If it is determined that the harm outweighs the public interest in disclosure, the request is denied and the information remains confidential.

Basically, Netflix was trying to force the CRTC into a corner today over this issue, and Blais was not having any of it.

Lastly, the CRTC’s Digital Media Exemption Order under which Netflix and other OTT providers operate in Canada albeit exempt from the normal requirements of the Broadcasting Act, makes it clear that such companies are required to submit information regarding their “activities in broadcasting in digital media, and such other information that is required by the Commission in order to monitor the development of broadcasting in digital media”.

Some may not like these requirements, but for the time being they are the rules of the game and having decided to play by the rules of the game since its entry into Canada in 2010, today’s hearing was not the right place for Netflix to challenge them.

We must remember that, since its first New Media Order in 1999, the CRTC has always claimed regulatory authority over television and other broadcasts delivered over the internet but has exempted them from the requirements of the Broadcast Act. It did so on grounds of technological neutrality, fostering creativity and innovation and that doing so would not prove disastrous to the Canadian “broadcast system”. In short, it is not whether the CRTC can regulate the internet broadcasting, as Michael Geist noted the other day, but will it? The answer has unambiguously been yes, the CRTC can regulate internet broadcasting, but will not for the time being. That was the answer in 1999, in 2009 and in its last statement on the matter, the Digital Media Exemption Order (2012).

Three final points. First, Netflix cannot cherry pick the elements of Canadian media and telecoms policy that serve it while cocking a snook at those elements it would rather not deal with. Netflix has been the beneficiary of the CRTC’s robust network neutrality rules, rules that apply both to wiredline telecoms and mobile wireless telecoms providers. This has been a huge benefit to Netflix, and partly on account of such measures its ability to locate its content caching equipment at Canadian telecoms and ISP providers such as Bell, Rogers, Telus and Shaw are a far cry easier in Canada than in the US. The forthcoming CRTC Mobile TV proceeding will help to determine the utility of these rules.

As Netflix does battle in the US at the FCC hearings now taking place over the future of network neutrality in that country, it would do well to recall the comparably better conditions it has in Canada. As Netflix itself noted today, Canada is its best international market and I would suggest that the combination of the CRTC’s network neutrality and light touch Digital Media Exemption Order help explain this state of affairs. As such, when the Commission asks for information and to trust that it will make the proper decision in weighing the company’s claims for confidentiality with the benefits of public disclosure, Netflix would do well to play ball.

Third, Netflix also needs to recognize that, faced with a wall of claims from incumbents for two week’s running that unregulated OTT services threaten the Canadian “television system” altogether, robust evidence could help put such self-serving claims in perspective and is just what the CRTC needs. Indeed, Netflix should meet the CRTC’s deadline for its orders for information of this Monday to help in just this regard, otherwise the CRTC will be left with much self-serving bluster about falling skies and doom and gloom.

Finally, it’s time to recognize that while I don’t personally think that Netflix should be subject to all of the requirements of the Broadcasting Act, this is no longer the days when technophiles could see the Internet as an unregulable space. Those days were always an illusion and, regardless, are over. There is a discussion to be had, and that discussion is already underway in many other countries around the world, as Netflix knows full well.

Outside Canada, the European Union’s Audiovisual Media Services Directive brought online video providers under its sway in 2010. The Dutch and France have also reportedly required it to torque its algorithms to give priority to local content and to contribute to the creation and circulation of television content from both countries and Europe as a whole.

Whether we agree with that or not, it’s now the discussion to be had, rather than ducked with gestures towards the internet as some kind of nirvana that exists outside the normal laws of the land. Neither Netflix, Google nor any other ‘digital media giant’ can escape this reality by invoking the internet as an world beyond regulation when they please while calling for network neutrality when that suits. What we all need to realize, is that an open media requires smart regulation not no regulation.

The Growth of the Network Media Economy in Canada, 1984-2012

Cross-posted from the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project blog.

Has the media economy in Canada become bigger or smaller over time? Does the answer to that question, one way or the other, apply across the board, or to only a few of the dozen or sectors that make up the network media economy: i.e. wireline and wireless telecoms; internet access; cable, satellite & IPTV; pay and specialty television; conventional television; radio; newspapers; magazines; music; search engines; social media; internet advertising and online news sources?

Which of these sectors are growing, which are stagnating and which are in decline? To illustrate these trends over the period from 1984 until 2012, this post hones in on rising new media services (IPTV), those that have seen their revenues stay relatively flat over the past few years (conventional television) and those that appear to be in long-term decline (newspapers). I also examine whether the media economy in Canada is big or small relative to global standards.

This post also aims to set down a baseline of data to underpin a series of posts to follow over the next few weeks. Similar to what I have done for the past two years, the next post examines trends within and across the TMI industries from 1984 until 2012 to see if they have become more concentrated over time, or less (for previous versions, see here and here). The post after that zooms in on the top sixteen or so companies with one percent or more market share across the network media in Canada. Such firms account for 86% of all telecom, media and internet revenues. Rank ordered on the basis of revenue, they are: BCE, Rogers, Telus, Shaw, Quebecor, the CBC, MTS, Cogeco, Google, Torstar, Sasktel, Postmedia, Astral, Eastlink, the Globe and Mail, Facebook and Netflix. You can see a past version this discussion here).

In addition to updating our analysis for a complete set of the 2012 data, our goal is to break new ground. This year we do so by adding a new post that examines the state of media, telecom and internet concentration in Canada relative to the preliminary results of a thirty country study by the International Media Concentration Research Project, in which I served as the lead Canadian researcher. There are some surprising results that that smash a few shibboleths while confirming other elements of what we know from past research.

Finally, another new dimension for this year is a break out of data and analysis for the English- and French-language telecom, media and internet (TMI) markets. For the most part, similar questions to those introduced above are addressed about media growth and concentration trends between 2000 and 2012, while the leading firms in both of these regions are profiled in terms of size, ownership, the media, telecom and internet sectors they operate in, and how they each fit into the Canadian mediascape overall. 1

While we cite our sources below, by and large, the following documents and data sets underpin the analysis in this post: Media Industry Data, Media Economy Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

Canada’s Network Media Economy in a Global Context

Canada’s network media economy has grown immensely over time. Between 1984 and 2012, it nearly quadrupled from $19.4 billion in revenue to $73.3 billion (current $). Adjusted for inflation, the rise was from $39 billion to $73.3 billion last year (2012 $).

While often cast as a dwarf amongst giants, the network media economy in Canada is large by international standards: tenth largest in the world as of 2012, as the overview in Table 1 below illustrates.

Table 1: Canada’s Ranking Amongst 12 Biggest Network Media Economies by Country, 1998 – 2012 (billions USD)

Sources and Notes: OECD Communication Outlook 2013; ITU Revenues 2012. PriceWaterhouseCooper’s Global Entertainment and Media Outlook, 2012 – 2016 (plus 2011, 2010 and 2009 editions) for media and internet. P = preliminary estimate for countries, except Canada. See CMCRP Media Industry Data and methodology primer for Canadian data and analysis.

Canada’s network media economy is obviously small relative to the U.S., at one-twelfth the size. However, relative to the rest of the world, it is amongst the biggest, right after Australia, Italy and Brazil and just ahead of Spain and South Korea.

The growth of the network media economy was especially swift from the early-1990s well into the first decade of the 21st century but like most other countries on the list, it has slowed since 2008, mostly on account of the economic instability that has followed quick on the heels of the Anglo European financial crisis (2007ff). Indeed, worldwide network media revenues fell 5% between 2008 and 2009 and half of the countries listed in Table 1 saw their media economies actually shrink over the following years: the US, Germany, France, the UK, Italy and Spain.

Collectively, these countries’ media economies shrank by around $67.2 billion between 2008 and 2012. Some of this lost ground was regained by 2011, but only on account of increases in the US and France while the media economies in the other four countries (Germany, the UK, Italy and Spain) continued to be smaller than they were before the financial crisis.

In sharp contrast to much of Europe, the US and, less so, Canada, the media economies of Australia, South Korea, Brazil and China have been largely unscathed by the financial crisis. Indeed, these countries and a few others such as Turkey, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Russia have been going through something of a ‘golden media age’ over the past decade, with most media, from internet access, to the press, television, film and so on undergoing an unprecedented phase of fast-paced development (OECD, 2010).

The Network Media Economy in Canada: Growth, Stagnation or Decline?

As noted above, the network media economy in Canada has grown enormously from $19.4 billion in 1984 to nearly $73.3 billion in 2012 (current $), or from $39 billion in 1984 to just over $73.3 billion last year (2012$). Figure 1 below charts the trends using current dollars.

Source: see Media Economy Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

Entirely new sectors – wireless, internet access, pay and specialty tv services, internet advertising – have added immensely to the increase. The most significant source of growth is from the platform media elements (wireless, ISPs, IPTV, cable and satellite), especially after the mid-1990s, but television has also grown enormously regardless of where we start the time line.

Music has also grown slightly, at least once a full measure of all of its subsectors are included – recorded, live, digital/online and publishing – as shown below, while radio has stayed mostly flat. In contrast, wireline telecoms, newspapers and magazines have declined, the first very sharply since 2000 and the latter two gently since sometime between 2004 and 2008, depending on whether trends are looked at from the point of view of real dollars or current dollars.

Table 2 below summarizes the state of affairs across the network media economy as things stood at the end of 2012 in terms of whether each sector covered in this post appears to be growing, stagnating or in decline.

Table 2: The Network Media in Canada: Sectors Experiencing Growth, Stagnation or Decline

The Platform Media Industries

The platform media industries – the pipes, bandwidth and spectrum used to connect people to one another and to devices, content, the internet, and so on — of the network media economy grew from $13.8 billion to $51.5 billion between 1984 and 2012. In real dollar terms, revenue grew from $26.8 billion to $52.5 billion. Table 3 shows the trends.

Table 3: Revenues for the Platform Media Industries, 1984 – 2012

Sources: see Media Economy Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

Accounting for 72% of revenues, the platform media sectors are the fulcrum of the media economy, as is the case in most of the world. This is why Bell, Rogers, Shaw, Quebecor, Telus, SaskTel, MTS Allstream, Eastlink, Cogeco, etc. are so fundamental to the media economy.

While some might think that the over-sized weight of the platform media in the media economy is of recent vintage, their share of the network media economy in 2012 was basically the same as it was in 1984, i.e. 71-72%, albeit within the context of a vastly larger media economy. This is mostly because of the steep decline in wireline telecom revenues, from $21.2 billion at their peak in 2000 to $15.9 billion in 2012.

As plain old telephone service (POTS) has gone into decline, however, some pretty awesome new stuff (PANS) has come along to more than pick up the slack. Wireless is the best example of this, with revenues skyrocketing after 1996, as Figure 1 and Table 2, above, demonstrate.

Indeed, wireless revenues have nearly quadrupled from $5.4 billion in 2000 to $20.3 billion last year. A corresponding rapid growth in mobile voice and data traffic reinforce the impression. Voice and data traffic were up in Canada 69% and 85% in 2012 over 2011, respectively, with the latter rising considerably faster than the worldwide average (70%)(sources cited here are silent on the other).

The growth in wireless is fast on account of the expanding array of devices that people use to connect to wireless networks: phones, smartphones, tablets, wifi connected PCs, and so on. In short, personal wireless mobile communications are quickly moving to the centre of the media universe. These are the social, economic and technological foundations underpinning the wireless wars that are now in full-swing in Canada.

Some have recently argued that the rate of wireless growth has slowed since 2008, arguing that this is mainly because it is becoming a mature market (Church and Wilkins, 2013, p. 40). Relative to the torrid pace of growth from the late-1990s through the most of the 2000s, this is true. However, it is well known that the pace set during the early commercialization of new technologies cannot be sustained forever. More than this, however, the flattening of growth coincides perfectly with the financial crisis.

This reality simply cannot be ignored. As indicated earlier, revenues for the network media economy worldwide declined between 2008 and 2009 and many of the world’s largest network media economies are still smaller today than they were five years ago (Germany, UK, Italy and Spain), have stalled (Japan and France) or are only modestly larger now than they were five years ago (US, Canada and Korea). Therefore, a modest let-up in the pace of wireless growth amidst such conditions is not surprising.

That said, wireless revenues have not been hit as hard as other media sectors by either the collapse of the dot.com bubble in 2000 or by the Anglo-European financial crisis (2007ff). Only the pace of development has slowed relative to past trends.

Internet access displays similar patterns of massive growth, albeit for not as long or to the same extent. Internet access revenues last year were $7.6 billion, up substantially from $6.2 billion in 2008 and quadruple what they were at the turn-of-the-21st century ($1.8 billion).

The most notable development in the past two years is the rapid growth of the telephone companies’ Internet Protocol TV (IPTV) services, albeit from a low base. IPTV is the incumbent telcos’ managed internet-based tv services: e.g. Telus, Bell, MTS Allstream, SaskTel, and Bell Aliant. Revenues have nearly tripled, from $231 million to $638 million, over the past two years. The number of IPTV subscribers has followed suit, rising sharply from 200,000 in 2008, to nearly a half-million at the end of 2010, to just under 1.2 million at the end of 2012.

These figures are slightly higher than those in the CRTC’s Communication Monitoring Report (pp. 110-111) because the CRTC’s figures for subscribers are taken from the end of August in each year as opposed to the end of the year. More importantly, the CRTC’s estimated revenues (ARPU) are lower than those the telcos cite in their annual reports (see CMR, pp. 110-111).

Tables 4 and 5 below show the trends for IPTV growth in terms of both subscribers and revenues, respectively.

Table 4: The Growth of IPTV Subscribers in Canada, 2004–2012

|

2004 |

2006 |

2008 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

| Bell Fibe TV |

13,000 |

50,644 |

248,298 |

|||

| Bell Aliant |

46,575 |

68,199 |

107,391 |

|||

| Telus |

63,000 |

266,000 |

453,000 |

637000 |

||

| MTS Allstream |

25,422 |

59,442 |

82,278 |

89,604 |

93,244 |

95,374 |

| SaskTel |

22,850 |

48,980 |

68,408 |

83,610 |

91,854 |

93507 |

| Total IPTV Connections |

48,272.0 |

108,422 |

213,686 |

498,789 |

756,941 |

1,181,570 |

Sources: see Media Industry Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

Table 5: The Growth of IPTV Revenues in Canada, 2004–2012

|

|

2004 |

2006 |

2008 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

| Bell Fibe TV |

8.9 |

22.7 |

120.2 |

|||

| Bell Aliant |

14.9 |

27.6 |

55.7 |

|||

| Telus |

14.3 |

101.6 |

202.2 |

314.7 |

||

| MTS Allstream |

8.4 |

29 |

50 |

59.0 |

70.6 |

78.5 |

| SaskTel |

7.6 |

23.9 |

37.1 |

51 |

63.7 |

74.3 |

| Total IPTV $ |

16 |

52.9 |

97.2 |

231.3 |

380.0 |

638.1 |

Sources: see Media Industry Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

The growth of IPTV services is significant for many reasons. First, the telcos are finally making the investments needed to bring next generation, fiber-based internet networks closer to subscribers, mostly to neighbourhood nodes and sometimes right to people’s doorsteps. If the distribution of television is essential to the take-up of next generation networks, as I believe it is (for better or worse), IPTV will be a key part of the demand drivers for these networks (see below).

Second, the addition of IPTV as a new television distribution platform brings the telcos deeper into the cable companies’ dominion. IPTV services accounted for 7.5% of the TV distribution market in 2012 (the CRTC’s Communication Monitoring Report publishes a slightly lower number at 6.7%, p. 110 for reasons explained above). The competitive threat posed by IPTV services, however, is more prominent in the western provinces where Telus, SaskTel and MTS are deploying IPTV in direct rivalry with Shaw versus the provinces from Ontario to the Atlantic where Bell’s decision to manage the introduction of IPTV in ways that are as least disruptive to its existing satellite operations as possible has moderated the impact on Rogers, Quebecor and Cogeco.

While the telcos’ IPTV services appear to have cut into the revenues of some cable companies, they have also contributed to a substantial expansion of BDU revenues from $8.1 billion in 2010 to $8.7 billion last year. Growth in 2012, however, was slow. Against the hew and cry about cord-cutting in industry pleadings for regulatory favours, and in so much of the journalistic coverage that uncritically repeats such claims, the losses of a few incumbent cable providers should not be mistaken with an industry in peril. Even if it was, growing competition is to be encouraged rather than something to shed tears over.

While IPTV services finally appear to be taking off, we must remember several things. First, the small prairie telcos, followed by Telus, have taken the lead in deploying IPTV. For Sasktel, MTS and Telus, IPTV now make up a significant 13.9 percent, 6.6 percent and 5.9 percent, respectively, of their revenues from wireline network access services (Wiredline + ISP + Cable). Bell lags far behind, with 1.5 percent of its revenues coming from IPTV services, including Bell Aliant, in 2012 (see Table 5).

Indeed, Bell launched IPTV late via its affiliate Bell Aliant in 2009. It slowly rolled out service for the next two years in the high-end districts of Montreal and Toronto, half-a-decade after MTS and SaskTel began doing so in the prairies. More cities were added in 2012 and subscriber numbers for the Bell Fibe service grew as a result from just under 120,000 the year before to about 356,000.

Innovation and investment in Canada came first from small telcos on the margins and Telus, not Bell. This replays a long-standing practice for new services to start out as luxuries for the rich before a mixture of public, political and competitive pressures turn them into affordable and available necessities for the public generally (see Richard John with respect to the US, Robert Babe for Canada). From the telegraph to next generation fibre Internet infrastructure, the tendencies, conflicts and lessons have remained much the same. The wireless wars that are now in full-swing are just the latest iteration of an old, old story (Winseck Reconvergence, Winseck and Pike, John or Babe).

IPTV remains under-developed as a critical part of the network infrastructure in Canada, accounting for only 2 percent of the $32.2 billion in wire line network access revenues (i.e. wireline+BDUs+ISPs) (see Table 3 above). Less than two percent of broadband connections in Canada use fiber-to-the-home (see CMR, p. 142). The OECD average is 15 percent. In countries at the high end of the scale (Sweden, Slovak Rep., Korea, Japan), thirty to sixty percent of all broadband connections are fiber-based. The OECD ranks Canada 24 out of 34 countries in terms of fiber-connections out of the total number of subscribers as of December 2012. The following figure illustrates the point.

Figure 2: Percentage of Fibre Connections Out of Total Broadband Subscriptions (December 2012)

Source: OECD (2013). Broadband Portal.

For those who might be dismissive of such figures, it is useful to remember that the data presented in Tables 4 and 5 about IPTV are based on the Canadian telcos’ own audited numbers from their annual reports. While it has become something of a sport in Canada to cast aspersions on the OECD data (see here, here and here), the UK regulator Ofcom comes to similar conclusions: 5% of Canadian households subscribed to IPTV in 2011 versus France (28%), the Netherlands and Sweden (11%), Germany and the US (6%) and Spain (4%) as of 2011 (p. 136). The prairie telcos and Telus are part way to the OECD average, but in many ways, especially given its size and presence from Ontario to the Atlantic, it is Bell’s poor performance over the past half-decade that has dragged Canada down in the global league tables.

The Content Media Industries

The remainder of this post looks at the content media industries (broadcast tv, specialty and pay tv, radio, newspapers, magazines, music and internet advertising). For the most part, they too have grown substantially, although the picture has become murkier for a few sectors in the past few years.

In 1984, total revenue for the content industries was $5.6 billion; in 2012, it was $20.8 billion in 2012. In inflation-adjusted dollars, the revenues basically doubled from $11.3 billion to $20.8 billion over this span of time. Growth was steady throughout this period, with no discernible major uptick or downturn at any given point in time except for the years between 2008 and 2010, for reasons discussed above. Figure 3 depicts the trends.

Figure 3: Revenues for the Content Industries, 1984 – 2012 (Millions $)

Sources: Media Economy Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

The rise of the internet and the confluence of its impact with the advertising downturn after the Anglo European financial crisis led many to claim that conventional TV is in a death spiral. Over-the-top services such as Netflix and supposedly rampant cord-cutting further compound the woes, or at least so the story goes.

Such doomsday scenarios, however, have been wide of their mark. Advertising revenue has gyrated in lockstep with state of the economy: plummeting by 8.5% from 2008 to 2009 followed by substantial increases of 9.2% and 7.7% in 2011. Things, however, stalled in 2012 amid ongoing economic uncertainty (-2%), fitting the patterns described earlier perfectly (on economic recessions, advertising revenue and the media economy see Picard, Garnham or Miege).

Beyond advertising, the picture is clearer. The amount of time people watch television has stayed remarkably steady across all age groups and outstrips time with other media — the internet, radio, newspapers or other media – by a considerable margin, according to the most recent Canadian Media Usage Study. Ofcom’s latest international monitoring report shows that TV viewing was up in 13 of the 16 countries it surveyed, including Canada (p. 162).

In “Why the Internet Won’t Kill TV”, Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. senior analyst Todd Juenger writes, “so far teens are following historical patterns, and in fact, their usage of traditional TV is increasing”. Their use of computers, smart phones and tablets to do so is adding to, rather than taking away from, how much they watch television, he states.

Internet equipment manufacturers Cisco and Sandvine suggest that television and online video are driving the evolution and architecture of the internet. The proliferation of devices is expanding the time and space for television in people’s lives, not taking away from it. Elsewhere, I have called this the rise of the prime time internet. The fact that Netflix is engineered to be viewed on 800 devices helps illustrate the point.(2)

Conventional broadcast TV revenues have been basically flat since 2008. In real dollar terms, they have slid from $3,562 million to $3,407 in 2012 – a 4% decline. The real growth has been in subscriber fees and the pay-per model of TV (Mosco), as has been the case around the world – a point returned to immediately below.

For now, however, four points can be highlighted to explain the stalled growth of conventional TV when measured in current dollars or slight decline when ‘real dollars’ are used:

- dip in TV advertising in 2012;

- budget cuts to the CBC (p. 8);

- the phasing out of the LPIF between 2012 and 2014;

- the big four commercial TV providers – Shaw, Bell, Rogers and Quebecor –backing of the rapidly growing pay, specialty and other subscriber-based forms of TV (i.e. mobile, IPTV), while edging away from broadcast TV (see the CRTC’s CMR, pp. 100-102 and Individual Financial Summaries for a list of the 116 pay and specialty channels the big four, in total, own 2012).

That the TV in crises choir is wide of the mark is clearer yet once we widen the lens to look at the fastest growing areas of television: i.e. specialty and pay tv services (HBO, TSN, Comedy Central, Food Network, etc), mobile TV, and television distribution. Pay and specialty television services have been fast growing segments since the mid-1990s and especially so during the past decade. Their revenues eclipsed those of conventional broadcasting in 2010, when revenues reached $3,474.6 million. Last year, that figure was half-a-billion dollars higher at $3,967.5 million.

Adding conventional as well as specialty and pay tv services together to get a sense of ‘total television’ revenue as a whole yields an unmistakable picture: total TV revenues quadrupled from $1,842 million in 1984 to $7,375 million in 2012; using ‘real dollars’, total TV revenues doubled from $3.7 billion to $7.4 billion last year — hardly the image of a media sector in crisis. The fact that such trends persisted steadfast in the face of the economic downturn also points to a crucial point: the importance of the direct pay-per model (Mosco) and its relative imperviousness to economic shocks in comparison to the hyper-twitchy character of advertising revenue.

Add cable, satellite and IPTV distribution and the trend is more undeniable. In these domains, as indicated earlier, the addition of new services, first DTH in the 1990s, followed by IPTV in the past few years, plus steady growth in cable TV, means that TV distribution has grown immensely. Indeed, revenues for these sectors expanded twelve-fold from $716.3 million in 1984 to $8,695.7 million in 2012 (in current dollars).

“Total TV” and TV distribution revenues accounted for just over $16.1 billion in 2012. To put this another way, in 1984, all segments of the TV industry accounted for just 7% of revenues in the network media economy. That figure rose to 14% in 2000; by 2012, it was 22%. Table 6 illustrates the trends.

Table 6: Television Moves to the Centre of the Network Media Universe, 1984 – 2012 (millions current $)

Sources: see Media Economy Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

Sources: see Media Economy Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

Television is not dead or dying. It is thriving, and remains at the core of the internet- and wireless-centric media universe. Moreover, television and online video are driving the development and use of wireless and internet services. This is why Rogers, Telus and Bell are all using television to drive the take-up of 4G wireless services, and IPTV for the latter two. To paraphrase Mark Twain, rumors of television’s demise are greatly exaggerated.

Of course, this does not mean that that life is easy for those in the television business. Indeed, all of these sectors continue to have to come to terms with an environment that is becoming structurally more differentiated because of new media, notably IPTV and over-the-top (OTT) services such as Netflix, as well as significant changes in how people use the multiplying media at their disposal.

While incumbent television providers have leaned heavily on the CRTC and Parliament to change the rules to bring OTT services into the regulatory fold, or to weaken the rules governing their own services (see Bell’s submission in its bid to take over Astral Media, for a recent example, notably p. 22), OTT services have not cannibalized the revenues of the industry. They have added to the size of the pie. Based on an estimated 1.6 million subscribers at the end of 2012, Netflix’s Canadian revenues were an estimated $134 million – about 1.8 percent of “Total TV” revenues. Reports by Media Technology Monitor and CBC as well as the CRTC’s (2011) Results of the Fact Finding Exercise on Over-the-Top Programming Services lead to a similar conclusion.

Part of the more structurally differentiated network media economy is also illustrated by the rapid growth of internet advertising. In 2012, internet advertising revenue grew to $3.1 billion, up from just over $2.7 billion a year earlier and $1.6 billion in 2008. At the beginning of the decade, internet advertising accounted for a comparably paltry $110 million, but has shot upwards since to reach current levels. Similar to wireless services, however, internet advertising revenues continue to grow fast, although even here the pace has slowed appreciably since the onset of the Euro American financial crisis.

To be sure, these trends have given rise to important new actors on the media scene in Canada, notably Google and Facebook, among others, who account for the lion’s share of internet advertising revenues. Indeed, based on common estimates that Google takes about half of all internet advertising revenues, the search engine giant’s revenues in Canada in 2012 were in the neighbourhood of $1,542.5 million.(3) This is significant. It is enough to rank Google as the eighth largest media company operating in Canada, just after the CBC and MTS, but ahead of, in rank order: Cogeco, Torstar, Sasktel Postmedia, Astral, Eastlink, Power Corporation (Gesca) and the Globe and Mail.

For its part, Facebook had an estimated 18.1 million users in Canada at the end of 2012. With each Canadian user worth about $12.70 to the company a year, it’s revenue can be estimated as having been $229.7 million in 2012, or 7.5% of online advertising revenue – an amount that gives it a modest place in the media economy in Canada and near the bottom of the list of the top twenty TMI companies in this country.

While it is commonplace to throw digital media giants into the mix of woes that are, erroneously, trotted out as bedeviling many of the traditional media in Canada, the fact of the matter is that Netflix’s impact on television revenues is negligible, while those of Google and Facebook are mostly irrelevant except for three areas where they are likely quite significant: music, magazines and newspapers. For the latter two, this is because of the direct impact on advertising revenues, while for music it is not advertising that is at issue, but how online distribution and the culture of linking is affecting the music industry. The following and concluding sections of this post sketch out trends in each of these domains.

Music

While many have held up the music industry as a poster child of the woes besetting ‘traditional media’ at the hands of digital media, the music industry in Canada is not in crisis. The picture over time, however, is mixed but getting better from a commercial standpoint.

Using current dollars, the sum of all of the main components of the music industry – i.e. recorded music, digital sales, concerts and publishing royalties – the music industry has grown modestly from $1,214 million in 1998 to $1,523.2 million in 2012. The current trend is slightly up, but the trend over the past decade-and-a-half has been unsteady, with considerable oscillation between record highs and contemporary lows.

Revenue dropped after the collapse of the dot.com bubble between 2000 and 2002, for instance, but then rose again until hitting a peak in 2004 of $1,379.3 million where they stayed flat for the next four years, when they began once again to climb. By 2010, music industry revenues had grown to $1,458.2 million; they have edged upwards from there ever since: to $1,480.4 million in 2011 and to $1,523.2 million last year – an all time high. Figure 4 illustrates the trends over time based on current dollars.

Figure 4: Total Music Revenues, 2000, 2006 & 2012 (millions$)

Sources: Recorded Music from Statistics Canada, Sound Recording and Music Publishing, Summary Statistics CANSIM TABLE 361-0005; Stats Can., Sound Recording: data tables, October 2005, catalogue no. 87F0008XIE; Stats Can, Sound Recording and Music Publishing, Cat. 87F0008X, 2009; except for 2012, from PriceWaterhouseCooper, Global Media and Entertainment Outlook, 13th ed., 2012; Concerts from Stats Can, Spectator sports, event promoters, agents, managers, and artists for 2007, 2008, and 2009; Publishing from Socan, Financial Report (various years); Internet from PriceWaterhouseCooper, Global Media and Entertainment Outlook, 13th ed (various yrs).

The picture is less rosy when we switch the metric to ‘real dollars’, which results in revenues reaching a high of $1.6 billion in 2004 before dropping to their lowest point in over a decade: $1, 455 million in 2008. Yet, since then, revenues have once again been on the rise and in 2012 reached $1523.2 million – less that 4% off their peak in 2004.

This is a slight decline since the all-time high in 2004, of course, but certainly not a calamity. Moreover, the trend from 2008, whether measured in current or real dollars is all in one direction: up! One reason for this might be because of all the media covered by the network media concept, the music industries embraced digital/internet sources of revenue earlier and more extensively than any other. Worldwide, by 2012, the industry obtained about 15% of its revenues from online, mobile and digital sources.

There is and has been no crisis in the music industry. In fact, conditions in Canada now mirror those in the music industry worldwide. To be sure, certain elements within the music industry – recorded music, for instance – have suffered badly, but publishing has plugged steadily along with modest increases and digital/online/mobile have exploded. Even recorded music now appears to be holding steady. Moreover, whereas recorded music has long been the centre of the industry that place has now been usurped by live concerts, as shown above. Even the music industry’s main lobby group, the International Federation of Phonographic Industries states in its most recent Digital Music Report that in 2012 “the music industry achieved its best year-on-year performance since 1998” (p. 5).

Radio

Radio stands in a similar position to the music industries a few years ago. Revenues grew until reaching a peak in 2008: $1,990 million (includes CBC annual appropriation), a level at which they have basically remained ever since. Revenues in 2012 were $1,946 (current dollars). Change the measurement from current dollars to inflation-adjusted, real dollars, however, and the picture changes, with revenue declining from $2,088.3 million in 2008 to $1,946 million in 2012 – a fall of 6.8%.

Magazines

Magazines appear to stand in the same position as the music and radio sectors as well, although I have not been able to update my revenue data for the sector for either 2011 or 2012. Yet, extrapolating from trends between 2008 and 2010 to obtain an estimate for 2012, revenues have declined slightly on the basis of current dollars (from 2,394 million in 2008 to $2,100 in 2012). PriceWaterhouseCooper, in contrast, shows a slight uptick in revenues between 2011 and 2012. Back to estimates using Statistics Canada and the drop of nearly 17 percent from $2,522.4 million in 2008 to $2,071.1 last year seems pronounced. The Internet Advertising Bureau shows a net drop in advertising between 2011 and 2012 of 3%. In other words, the evidence is mixed but leans toward the ‘media in decline’ side of the ledger.

Newspapers

Perhaps the most dramatic tale of doom and gloom within the network media economy, at least in terms of revenues, is from the experience of newspapers. Readers of this blog will know that in earlier versions of this post, and other posts, I have been skeptical of claims that journalism is in crisis. I still am. Generally, I agree with Yochai Benkler who argues that that we are in a period of heightened flux, but with the emergence of a new crop of commercial internet-based members of the press (the Tyee and Huffington Post, for example), the revival of the partisan press (e.g. Blogging Tories, Rabble.ca) as well as non-profits and cooperatives (e.g. the Dominion) and the rise of an important role for citizen journalists signs that journalism is not moribund or in a death spiral. In fact, these changes may herald a huge opportunity to improve the conditions of a free and responsible press.

At the same time, however, I also believe that traditional newspapers, whether the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star or Ottawa Citizen are important engines in the network media economy, serving as the content factories that produce news, opinion, gossip and cultural style markers that have the ability to set the agenda and whose stories cascade across the media in a way that is all out of proportion to the weight of the press in the media economy. In other words, the press originates far more stories and attention that the rest of the media pick up, whether television, radio or via the linking culture of the blogosphere, than its weight suggests. Thus, problems in the traditional press could pose significant problems for the media, citizens and audiences as a whole.

While I have been reluctant to see newspapers as being in crisis, mostly because in previous years I have felt that the trends had not been long enough in the making to draw that conclusion. I also believe that many of the wounds suffered by the newspaper business have been self-inflicted out of a mixture of hubris and badly conceived bouts of consolidation. Nonetheless, I began to change my tune last year and the results this year offer no reason to change course now.

The revenue figures for the newspaper industry, as one industry insider who tallies up the data told me, are “a mess”. The problems are mostly terminological in nature, such as how to define a daily, community or weekly newspaper while allocating revenue to each category accordingly. They also reflect concerns with how to present the industry in the least damaging light but without sugar-coating harsh realities. That said, using a mixture of data from Newspaper Canada and Statistics Canada allows us to arrive at good portrait of the newspaper industry over time and its main players, although it’s also important to point out that the Statistics Canada data for 2011 and 2012 are preliminary estimates that must wait until next year when it releases newspaper industry revenues for these years.

The data I use is drawn mostly from Statistics Canada, but Table 7 below shows both Newspaper Canada and Statistics Canada data so that readers can see the difference and also to reveal online revenues. Further discussion of why these differences exist can be seen in the relevant sections of the documents here and here.

Regardless of differences, both sources show that newspaper revenues have plummeted. In current dollar terms, Statistics Canada shows that newspaper revenues peaked at $5,482.3 million in 2008, and have fallen substantially since to an estimated $4,978 million last year. They fell another $180.7 million in 2012 – 3.6% — a decline of 12.5% since 2008. Table 7 illustrates the trends over time since 2004, while the full data set based on Statistics Canada data from 1984 can be seen under the relevant heading here.

Table 7: Newspaper Revenue — Newspapers Canada vs Statistics Canada, 2004-2012

| ($ million CND) | 2004 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

2012 |

| Daily Newspaper (Adv$) |

2,611 |

2,489 |

2,030 | 2,102 | 1,971 |

2,019 |

| Daily Newspaper (Circ$) |

745.1 |

808.3 |

867.2 | 836.9 | 829.5 |

829.5 |

| Community Newspaper ((Adv$) |

961 |

1,211 |

1,186 | 1,143 | 1,167 |

1,253 |

| Community Newspaper (Circ$) |

Total |

42.6 | 42.9 |

42.9p |

||

| Online Newspaper* |

– |

180.7 |

212.7 | 246.0 | 289.3 |

277.3 |

| Newspaper Canada |

4,317 |

4,689 |

4,509 | 4,616 | 4,589 |

4,422 |

| Statistics Canada Total $ |

5033.9 |

5482.3 |

4,938.5 | 5009.8 | 4978.5 |

4797.8 |

Sources: see Media Economy Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary. Online Newspaper revenues includes daily and community papers. 2012 data for Community Newspaper circulation revenue based on estimate of flat year-over-year growth.

In real dollar terms, the fall is more pronounced, with the decline setting in earlier and the drop being steeper. According to this measure, newspaper revenues basically flatlined between 2000 and 2008, with a small drop, but have shrunk greatly since by just under $1 billion – or 17%. This is the most clear cut case of a medium in decline out of the sectors of the network media economy reviewed in this post.

The results of these trends in 2012 were clear:

- Postmedia cut the Sunday edition at three of its papers (the Calgary Herald, Edmonton Journal and Ottawa Citizen) adding to those where such measures had already been taken in the past few years (e.g. the National Post);

- Postmedia also made deep cuts to journalistic staff across its chain;

- the Globe and Mail adopted a voluntary program with the hope that sixty of its journalists would take the hint and leave (and here);

- Quebecor’s Sun newspapers cut 500 jobs and centralized its printing operations in a smaller number of locations;

- Glacier and Black swapped a number of smaller papers to consolidate their own operations.

Perhaps the most significant change to take place in 2012 is the extent to which dailies were put behind paywalls in Canada. Prior to 2011 there were no dailies with paywalls; in 2011 there were 5 covering under 1/5th of daily circulation; by 2012 the number had grown to 11 dailies and more than half of daily circulation. By August 2013, the number had grown 26 dailies accounting for more than two-thirds of daily circulation – a rate that is considerably higher than either the US or the UK (see Picard and Toughill). Table 8 illustrates the point.

Table 8: The Rise of the Great Paywalls of Canadian Newspapers, 2011-2013

| Newspaper | Lang | Paywall | Owner |

Weekly Total |

Daily Avg. |

| Times Colonist, Victoria | English | May 2011 | Glacier Media |

168,003 |

28,000 |

| Daily Gleaner, Fredericton | English | Nov 2011 | Brunswick News Inc. |

33,042 |

5,507 |

| Times-Transcript, Moncton | English | Nov 2011 | Brunswick News Inc. |

1,813,141 |

302,190 |

| New Brunswick Telegraph Journal | English | Nov 2011 | Brunswick News Inc. |

1,017,394 |

169,566 |

| Gazette Montreal | English | May 2011 | Postmedia |

288,639 |

48,107 |

| % Circ behind Paywall (2011) |

17.9 |

19.2 |

|||

| Vancouver Sun | English | Aug 2012 | Postmedia |

103,106 |

17,184 |

| Province, Vancouver | English | Aug 2012 | Postmedia |

184,485 |

30,747 |

| Ottawa Citizen* | English | Aug 2012 | Postmedia |

313,017 |

52,169 |

| Journal de Montréal | French | Sept 2012 | Quebecor/Sun Media |

987,040 |

164,507 |

| Journal de Québec | French | Sept 2012 | Quebecor/Sun Media |

853,800 |

142,300 |

| Globe and Mail | English | Oct 2012 | Globemedia Inc. |

1,184,530 |

169,219 |

| Ottawa Sun | English | Dec 2012 | Quebecor/Sun Media |

106,343 |

17,724 |

| Toronto Sun | English | Dec 2012 | Quebecor/Sun Media |

683,327 |

113,888 |

| Winnipeg Sun | English | Dec 2012 | Quebecor/Sun Media |

764,473 |

109,210 |

| Calgary Sun | English | Dec 2012 | Quebecor/Sun Media |

853,800 |

142,300 |

| Edmonton Sun | English | Dec 2012 | Quebecor/Sun Media |

358,018 |

51,145 |

| % of Circ behind Paywall (2012) |

52.3 |

54.4 |

|||

| National Post | English | May 2013 | Postmedia |

2,503,284 |

357,612 |

| Calgary Herald | English | May 2013 | Postmedia |

987,040 |

164,507 |

| Edmonton Journal | English | May 2013 | Postmedia |

337,021 |

56,170 |

| Windsor Star | English | May 2013 | Postmedia |

1,015,625 |

145,089 |

| Guardian, Charlottetown | English | May 2013 | TC Media |

249,589 |

41,598 |

| Leader-Post, Regina | English | May 2013 | Postmedia |

337,021 |

56,170 |

| StarPhoenix, Saskatoon | English | May 2013 | Postmedia |

358,018 |

51,145 |

| The Daily News, Truro | English | July 2013 | TC Media |

290,101 |

41,443 |

| Toronto Star | English | Aug 2013 | Torstar Corporation |

2,014,592 |

287,799 |

| Chronicle-Herald, Halifax | English | Aug 2013 | Halifax Herald Ltd. |

770,132 |

110,019 |

| Total Circulation |

18,574,648 |

2,875,390 |

|||

| % of Circ behind Paywall (8/2013) |

68.8 |

68.3 |

Source: Newspaper Canada 2012 Daily Circulation Report.

Some Concluding Comments and Observations

Several observations and conclusions stand out from this analysis.

First, the network media economy has grown immensely over time, whether we look at things in the short-, medium- or long-term. In the short- to medium-term (1-5 years), however, things have been less rosy. The effects of the economic downturn in the wake of the Euro-American centred financial crisis have hit every sector, except, it would appear, and ironically, music, which began to recover shortly afterwards. Otherwise, the effect has been to slow the rate of growth in the fastest growing sectors (wireless, ISPs, internet advertising, television) and to compound the problem in those media already under stress (newspapers, magazines and radio).

Second, while the network media economy in Canada may be small relative to the U.S., it is large relative to global standards. In fact, it is the tenth biggest media economy in the world.

Third, while most sectors of the media have grown substantially, and the network media economy has become structurally more complex on account of the rise of new segments of the media, a few segments have stagnated in the past few years (broadcast TV, radio and music, with apparent light at the end of the tunnel in the last few years with respect to the latter). It is now safe to say that two sectors appear to be in long-term decline: the traditional newspaper industry and wiredline telecoms. Magazines probably fit the latter designation but it may still be too early to tell, with some good sources suggesting that it too, like the music sector, might be poised for a turn-around.

These ambiguities give good reason for why the CMCR project will continue to update our research on these matters annually. As we have said before, we can know of few better ways to gain an intimate understanding of our objects of analysis – the network media and all of its constituent elements – than to peer deeply and systematically into the data, while providing a theoretically and historically informed analysis of the data and trends that emerge over as long a period of time as we reasonably can.

1 Brazil telecom estimated at 12.5 percent growth from 2004 to 2008, and 5 percent per annum for 2010 through 201; China’s revenue estimated for 2010-2012 based http://www.cmcrp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Sources-and-Explanatory-Notes.docxon 10 percent per annum growth rates. Internet access revenues before 2004 are estimated for each country, except Australia and Canada, based on the prevailing CAGR for this sector within each country at the time.

2 Corey Wright, Director of Global Public Policy, Netflix, guest lecture given at School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University, September 2013.

3 The Globe and Mail’s publisher, Phillip Crawley told the World Publishing Expo in Berlin that Google takes 60% of internet advertising in Canada. Evidence for this claim do not seem to have been presented, but I am all ears if a good case can be made for revising the estimates upwards to this figure.

The ITU and the Real Threats to the Internet, Part IV: the Triumph of State Security and Proposed Changes to the ITRs

This is the fourth in a series of posts on the potential implications of proposed changes and additions to the ITU’s international telecommunications regulations (ITRs) on the internet (earlier posts are here, here and here).

As we assess these potential implications it is necessary to sort out charges that are, in my view, overblown and alarmist versus those that have merit based on a close reading of the relevant ITU texts. I want to be clear that while I think that many of the charges being leveled at the ITU are trumped up baloney, there are actually many reasons to be concerned. I’ll briefly reprise what I see as the over blown claims (OBCs), then set out the most important real areas of concern.

Over Blown Claims (OBC)

(OBC1): The ITU & the Net: The claim that new rules being proposed for the WCIT this December could give the ITU authority over the internet, when currently it has none, is one OBC (see here, here and here), as I laid out in blog post two.

(OBC2) The Global Internet Tax: This is the claim that some countries want to meter internet traffic at their borders, a kind of tax that Facebook, Google, Apple, Netflix and other internet content companies would supposedly be forced to pay to reach users on the other side of the toll – simultaneously serving to fund broadband internet upgrades in foreign countries, constricting the free flow of info, and keeping people sealed off behind the closed and controlled Web 3.0 national internet spaces that are being built in Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, Iran and other repressive states (see here and here).

The kernal of truth in this matter is that European telecom operators have proposed to establish a “fee-for-carriage” model – like cable tv – that would allow them to charge big internet content companies according to the volume of traffic they generate. I don’t like it at all. It is a full-scale assault on network neutrality. Google hates it too (Ryan & Glick, Cerf NYT, Cerf Congress). Net neutrality folks should be up in arms, and some are.

The problem at the root of the critics’ assertions, however, is that the proposal by ETNO is not unusual but embodies the same “fee-for-carriage” model that telecom carriers such as AT&T, Comcast, Bell, Telecom NZ, and others have pursued for the past decade (see post 3). It is wrong to construe the demand to make internet companies pay for carriage as a tax, let alone a diabolical scheme by authoritarian governments to take-over the internet.

In addition, the idea of an internet metered at the border overlooks possible additions to Art. 3.7 of the ITRs that, as discussed in the last post, “enabl[e] direct international internet connections” between countries. “Special Arrangements” set out in Art. 9 of the constitution also means that telecom and internet companies can strike whatever deals they want to create end-to-end connectivity, so long as both countries on either end agree. Again, markets and contracts rule, not some kind of cyber-wall of Berlin.

(OBC3) Spam, Spam, Spam: The third, mostly bogus claim is that proposals to add references to spam in several places in the ITRs are the thin edge of a wedge that could lead to internet content regulation (Article 2.13; Art. 4.3a; and proposed new Art. 8A.5 and 8B). The proposal, however, urges countries to adopt “national legislation” covering spam – as many already do – and “to cooperate to take actions to counter spam” and “to exchange information on national findings/actions to counter spam”. This hardly seems like the thin of a wedge and, moreover, Article 2.13 explicitly excludes content as well as “meaningful . . . information of any type”.

Still, the U.S. is strongly opposed to such measures on the grounds that technological solutions are better suited to the problem than international law. Overkill, it says, and at odds with technological neutrality. Australia calls it too broad, Canada doesn’t like it either, and Portugal is still looking to see how it meshes with EU law. This is hardly an endorsement for the ‘global regulation of spam’ by the supposed axis of internet evil offering it, but the proposal is hardly tantamount to Armageddon, either (for annotated notes outlining countries’ views of proposed changes and additions, see here).

State Security, Splinternet and the Pending Death of the Open Global Internet: the Real Threats to the Internet

Now if you think I’m simply lining up as an apologist for the ITU, you’d be wrong, as the rest of this post makes clear. Several proposals now on the table (see below) would cast a devastating blow to the internet by blessing the efforts of individual countries to build their own closed and controlled national Web 3.0 internet spaces today. In fact, many countries, including Anglo-European countries, are doing just that, although to a degree and of a kind that is demonstrably different than what is being built in the list of ‘rogue states’ that are often identified with such projects: Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, Iran, etc.

In fact, several sections of the ITU’s current framework already allow these kinds of projects, before any changes. Proposals to change or add new elements to the ITRs could make matters even worse, however.

Intercepting, Suspending and Blocking the Flow of Information since the 1850s: the Dark Side of the ITU

To see how, we need only to realize that nation-states have always claimed unbridled power to control national communication spaces, and to intercept, suspend and block the cross-border flow of information. The authority to inspect, suspend and cut-off communications that “appear dangerous to the security of the State or contrary to its laws, to public order or to decency” was first asserted by European governments in the 1850s during their drive to squelch popular rebellions. That authority was acknowledged by the Austro-German Telegraph Union and Western European Telegraph Union at the time, before being folded into the ITU when these organizations merged in 1865 (see Constitution, Article 34). That legacy hangs over the current WCIT talks like a dark cloud.

The supremacy of national security has been retained ever since and forms the basis of Articles 34, 35 and 37 in the ITU’s current Constitution, as the extracts below illustrate:

“Member States reserve the right to stop . . . the transmission of any private telegram which may appear dangerous to the security of the State or contrary to its laws, to public order or to decency” (Art. 34(1), Stoppage of Telecommunications, emphasis added).

“Member States also reserve the right to cut off, in accordance with their national law, any other private telecommunications which may appear dangerous to the security of the State or contrary to its laws, to public order or to decency” (Art. 34(2) Stoppage of Telecommunications, emphasis added).

“Each Member State reserves the right to suspend the international telecommunication service, either generally or only for certain relations and/or for certain kinds of correspondence” (Art. 35, Suspension of Services, emphasis added).

“Member States agree to take all possible measures . . . to ensur[e] the secrecy of international correspondence[, but] . . . reserve the right to communicate such correspondence to the competent authorities in order to ensure the application of their national laws or the execution of international conventions to which they are parties” (Art. 37, Secrecy of Telecommunications).

One proposal by the United Arab Emirates aims to replicate these measures in three new clauses to be added to the ITRs (Art. 7.3, 7.5 and 7.6, respectively), allowing such norms to do double-duty as high-level principles and day-to-day regulatory guidelines. The U.S. opposes the move, not because it sees telecoms and internet as a kind of global commons beyond the reach of harsh geopolitical concerns, but likely because the ITU already reflects the fact that national security concerns trump everything, and because it would not be unduly constrained by global norms anyway. The US response to the UAE proposal is clear on the point: “We support retaining these provisions in the CS [constitution] and do not agree with . . . duplicating them in the ITRs”.

Cyberwar and the Fifth Domain of Battle: Militarization of the Internet versus Global Commons

The U.S. also refuses to be drawn into the proposals bandied about by Russia (mostly), China and a few other powerful military states over the past decade, this time to add a sprawling new section to the ITRs covering cybercrime, national security and cyberwar issues (Article 8A). The U.S. has rebuffed these moves for the same reasons mentioned above and, more to the point, because behind the veil of its global-internet-freedom-as- foreign-policy rhetoric is its more pressing conviction that the internet is now the fifth domain of war, alongside land, sea, air and space, a terrain where it grandiosely seeks to assert total infosphere dominance.

Seen in this context, overtures to “network defense and response to cyberattacks” (Article 8A.1) have no chance of adoption, even if setting aside the internet as a global commons under ITU protection outside the field of war might be a good idea. Moreover, and however, that rubicon has already been crossed with Russia believed to have been behind cyber-attacks against Georgia in 2008 and the Obama Administration’s recent admission that it played a role in the Stuxnet attacks against Iranian nuclear facilities.

Bearing those points in mind, Russian proposals to carve out new rules of cyberwar are hypocrisy, while the acknowledged facts of U.S. military policy means that it will dismiss such notions out of hand. Based on this, worries that additions to the ITRs intended to deal with such matters could serve as a Trojan horse for repressive controls over the internet can probably be safely tossed aside. It is worth noting, however, that amidst all the hand-wringing over the ITU threat to the internet, no one, as far as I know, touches upon how the hard realities of military power shape global telecom and internet policy, instead settling into numbing nostrums that pit the state against the individual.

A Laundry List of Many Items with Potentially Really Big Implications

Beyond the stance of the U.S. on the above matters, and questions of network defense and cyberwar, Article 8A starts off innocently enough, but quickly opens into a chamber house of horrors. It blandly refers to “confidence and security” in the title and the need to garner trust in online spaces (true enough), followed by a list of technical-sounding proposals about network security, data retention, data protection, fraud, spam, and so on.

Some of these principles are worthy of discussion, but the way they have been teed up for WCIT utterly fails to inspire confidence or hope. The measures are spearheaded by Russia and supported by China, with the latter telling us in the notes accompanying the proposals that new tools and rules are needed to:

“. . . protect the security of ICT infrastructure, misuse of ICTs, respect and protection of user information, build a fair, secure and trustworthy cyberspace . . . [with] new articles on network security in the ITRs”.

There is also a sundry list of other items included in the proposed new Article 8A as well as others drawn from recommendations at past conferences that deal with child online protection, fraud, user identity, etc. One by one, most of these measures are reasonable, and most countries are dealing, on their own and in cooperation with one another, with all of them already.

Looking across all these proposals, however, reveals a raft of threats that, in their entirety, would usher in the foundation of controlled and closed national internet spaces that are subordinate to the unbound power of the state in every way:

- Anonymity and Online Identity are implicated in repeated references to the need for users to have a recognized identity. This comports well with laws in countries such as China that require internet users to tie their online identity to the ‘real-name’ identity but if identifiability is the first step to regulability, as Lawrence Lessig claimed a decade ago, than this raft of references insisting on the need for online identity is a problem (e.g. proposed new Art. 3.6, 6.10, 8A.7, 8A.8). As ISOC states, such moves entail a “very active and inappropriate role in patrolling newly defined standards of behaviour on telecommunication and internet networks and in services”. I agree;